Note: This page summarizes the rationale behind a GiveWell grant to J-PAL Africa. J-PAL Africa staff reviewed this page prior to publication.

Summary

In October 2024, GiveWell recommended a ~$470,000 grant to J-PAL Africa (“J-PAL”) to conduct scoping and stakeholder engagement to promote chlorine vouchers in high-burden countries. The overall aim of the grant is to unlock opportunities to fund future chlorine vouchers programs in those countries.

We recommended this grant because:

- We think chlorine vouchers programs are a promising way to reduce child mortality in locations with a high burden of waterborne disease. But we have not had opportunities to fund them at a significant scale to date.

- We expect this grant could unlock opportunities to fund future chlorine vouchers programs in high-burden locations. This is because:

- The J-PAL team that will be implementing this grant includes Pascaline Dupas, the lead author of both academic papers that our vouchers research relies on.

- We believe the J-PAL team has a promising track record of engaging government interest in delivering vouchers programs.

We see both of these factors as plausibly increasing the likelihood that governments will be interested in piloting and scaling vouchers programs.

- Our cost-effectiveness analysis (which models the impact of unlocking future opportunities to fund vouchers programs, and therefore enabling GiveWell to redirect funds in a more impactful direction) suggests that this grant is 19x as cost-effective as direct cash transfers (GiveWell’s benchmark for comparing different programs), vs our threshold of 10x. While we see this estimate as extremely rough, it supports our intuition that this grant is plausibly a highly cost-effective use of funding.

Reservations and uncertainties:

- It’s possible that this grant is duplicating work that would have happened anyway (e.g. because some opportunities to fund vouchers programs would have arisen through J-PAL’s existing relationships with country governments).

- J-PAL has proposed a light-touch staffing model for any vouchers programs it eventually supports. We’d expect this to increase the risk that the program might be delivered to a lower quality than the studies where chlorine vouchers were successfully tested (where researchers provided more intensive support).

- We don’t have much previous experience working with J-PAL. All else equal, we see working with partners we haven’t worked with before as riskier. In this case, one factor informing our thinking is that we see J-PAL as having relatively less experience of program implementation than research.

Published: March 2025

1. The organization

The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) is a research organization focused on using evidence to reduce global poverty.1 J-PAL Africa is an arm of J-PAL, based at the University of Cape Town, that leads J-PAL’s work in sub-Saharan Africa.2 As a shorthand, we refer to J-PAL Africa as “J-PAL” throughout this page.

2. The intervention

Chlorine vouchers programs involve distributing vouchers that parents of young children can redeem for bottles of chlorine solution, to treat water at home.3 GiveWell’s assessment is that there is moderately strong evidence that vouchers programs increase household chlorination rates based on two randomized controlled trials (RCTs), Dupas et al. 2016 and Dupas et al. 2023. Based on this evidence, we believe that vouchers programs have the potential to be cost-effective in high-burden locations, although we have not seen examples of scaled-up vouchers programs to date. See our vouchers intervention report and cost-effectiveness analysis for more details.4

We think household-level point-of-use chlorination is effective at averting mortality based on the same evidence that we use to evaluate other chlorination interventions that we have funded (dispensers for safe water and in-line chlorination). More in our water quality intervention report.

3. The grant

Scope: This grant will fund J-PAL to conduct scoping and stakeholder engagement work in countries (see below) that GiveWell sees as a high priority for implementing water chlorination programs (because of their high burden of under-5 mortality and waterborne disease). The overall aim is to unlock future opportunities to deliver chlorine vouchers programs in those countries, through engaging with governments and other stakeholders.

J-PAL will hire two policy managers who will conduct the following activities:5

- Desk research (e.g., on each country’s WASH6 infrastructure and prevalence of water treatment).

- Stakeholder mapping to understand the key actors (government departments, NGOs, chlorine suppliers, etc.) in each country.

- Relationship building, i.e., having meetings with government partners and other stakeholders to build interest in vouchers.

The project will be led by Dr. Pascaline Dupas7 , co-scientific director at J-PAL Africa,8 with additional academic support and expertise by Dr. Elisa M. Maffioli,9 although the grant does not directly fund their time.

This grant would only cover the initial scoping stage. If government interest materializes, GiveWell or another funder would need to make separate grants to fund J-PAL or another group to support implementation of the vouchers program in each country. We envisage vouchers programs would primarily be delivered through government-run health systems.

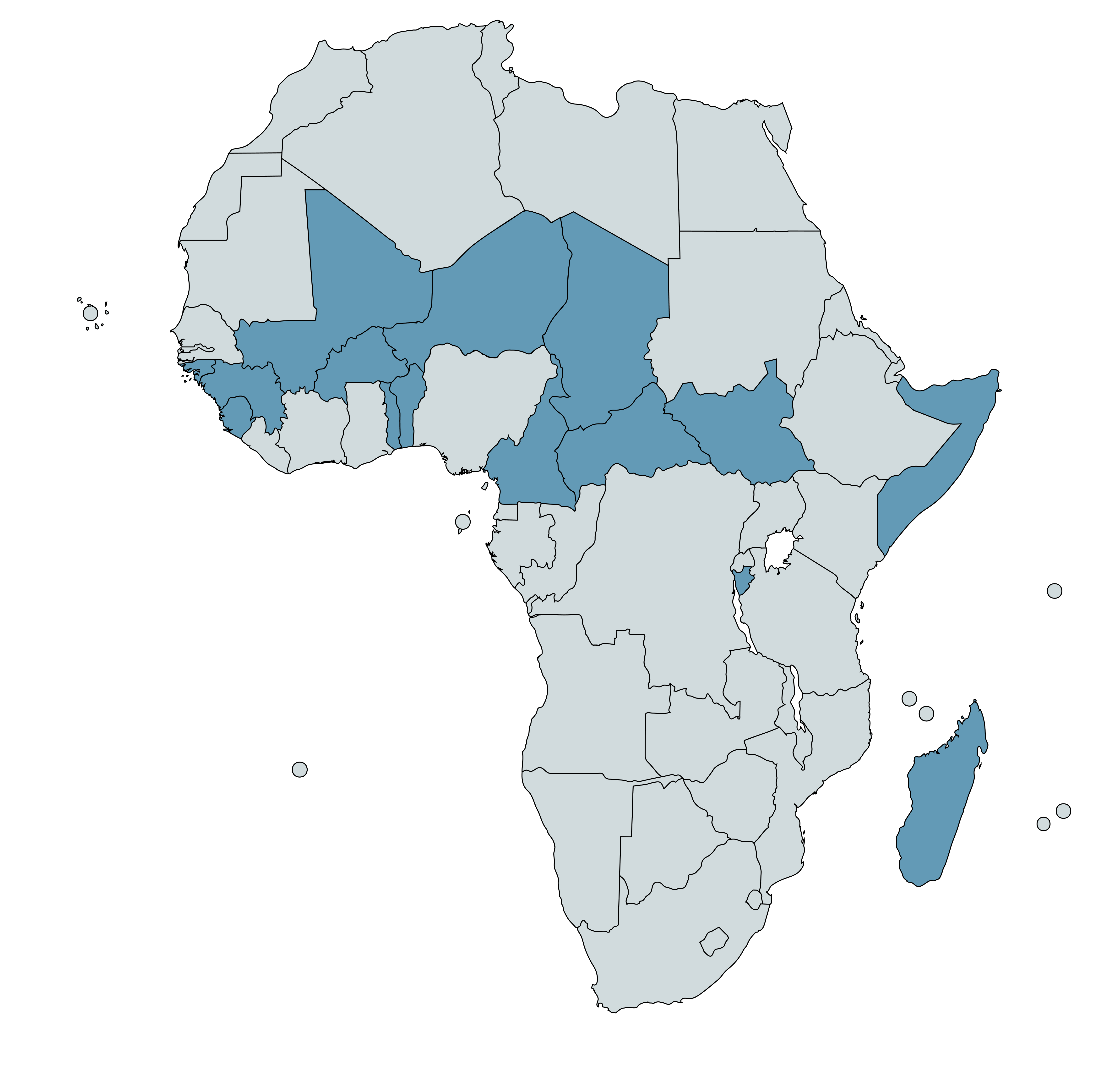

At the time we made the grant,10 we expected it to focus on the 15 countries11 highlighted in the map below. GiveWell selected these locations based on estimates of each country’s under-5 mortality and enteric infection mortality rates.12 We use these as rough proxies for locations where chlorination programs will be most impactful.13

Timeline: 18 months14

Budget: $472,36215

4. The case for the grant

We divide our reasoning into qualitative and quantitative factors. We put most weight on the former in our recommendation.

4.1 Qualitative case

- We see chlorine vouchers programs as promising in general. Chlorine vouchers are one of three chlorination programs (alongside dispensers for safe water and in-line chlorination) that we think could be impactful and we are actively pursuing opportunities to expand.16

Key reasons why we see vouchers as promising are:

- There is moderately strong evidence that vouchers programs can increase household chlorination rates based on two randomized controlled trials (RCTs).17

- The vouchers programs we’ve reviewed are low-cost and low-tech. We think it’s plausible that this could allow them to be delivered in low resource settings, without the need for substantial infrastructure investments.18

A key uncertainty is whether these programs can sustain high chlorination rates over time. We are also not aware of vouchers programs being delivered at substantial scale to date, and it’s possible that scaling up vouchers programs will be operationally challenging.19

- We expect this grant could unlock opportunities to fund chlorine vouchers programs in high-burden locations. This is because:

- We see J-PAL as well-connected and well placed to generate interest in vouchers among country governments. The team will be led by Pascaline Dupas, co-scientific director at J-PAL and the lead author of both chlorine vouchers RCTs that our analysis relies on.20 We expect that Dr. Dupas’ experience and credentials will increase the likelihood that governments will be interested in testing and scaling vouchers programs.

- J-PAL has a promising track record of getting governments engaged with vouchers. At the point we made the grant, J-PAL had recently begun work with the government of Rwanda on a vouchers program,21 and had also reported some interest among officials in other contexts incorporating vouchers into maternal and child health services.22

- This grant focuses on countries where we expect vouchers programs will be most impactful. It’s possible that we would otherwise not have opportunities to fund vouchers programs in these locations, e.g., because J-PAL has informed us it does not have existing government relationships in many of these countries,23 and because we’d expect difficulty of implementation and high security risk to correlate with high mortality burden.

- At the time we made the grant, GiveWell had also funded Evidence Action to deliver a vouchers pilot in Liberia to scope a possible pilot in Nigeria. However, Evidence Action told us it was unlikely in the short term to be able to deliver vouchers programs in some of the high burden countries included in this grant (e.g., Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali), where it does not have an existing presence.24

- This grant could allow us to get a deeper understanding of the overall landscape for chlorination programs in high-burden countries. As part of the grant, J-PAL staff will gather information about the landscape for chlorination programming in each country (e.g., existing water quality initiatives and government priorities). We think this could be valuable information as we try to expand our portfolio of chlorination programs (a relatively new area of grantmaking for GiveWell) even if we don’t have strong pre-existing hypotheses for exactly how.

4.2 Quantitative case

While we put most weight on the qualitative case for the grant, we also put together a rough cost-effectiveness analysis for this grant to provide a quantitative check on our assumptions. Our best estimate is that the grant is 19 times as cost-effective as direct cash transfers ("19x"), GiveWell’s benchmark for comparing different programs. At the time of writing this page, this is above GiveWell’s normal funding threshold (currently ~10x or more as cost-effective as cash transfers).25

Because the grant does not directly fund delivery of vouchers programs, we model the cost-effectiveness of the grant in terms of the “option value” it may create by unlocking opportunities to fund future vouchers programs in focus countries. Our best guess is that vouchers programs in these countries will be more cost-effective than our most likely alternative funding opportunities (17x for vouchers programs in these countries vs ~10x for alternative opportunities on average). We therefore model the grant as valuable by enabling GiveWell to redirect funds in a somewhat more impactful direction.

We see the intuitive case that the grant will be cost-effective as follows:

- The grant size is relatively small (~$0.47m for the initial grant, although more to fund the follow-on pilots that we need to realize any benefits).

- The pool of funding that it could influence is moderately large (we estimate up to ~$11m per year).

- The grant could allow GiveWell to divert funds in a significantly more cost-effective direction (from ~10x as cost-effective as direct cash transfers on average for alternative funding opportunities to ~17x on average for vouchers programs that this grant could unlock).

- The main thing depressing the grant’s cost-effectiveness is that this is only the first stage in a multi-stage process. For the grant to yield significant benefits, GiveWell would need to fund follow-on pilots, and those would need to be successful for substantial benefits to accrue. Factoring this in, our best guess is that only 4% of the population targeted by this grant will be reached by scaled-up vouchers programs.26 Even so, we still estimate the grant is a plausibly good use of funding because the potential benefits are high.

See our full cost-effectiveness analysis here and a simplified version below. Details on additional parameters and methods are in a footnote.27

| What we are estimating | Key parameters (rounded) |

|---|---|

| Grant size | |

| Total initial grant cost for scoping and stakeholder engagement ($m) | $0.47m |

| Total expected cost of follow-in pilots in countries expressing interest in the program ($m) | $0.52m |

| Subtotal: Total expected spending as a result of this grant | $0.99m |

| Potential value generated | |

| Expected cost-effectiveness of counterfactual opportunities (multiples of direct cash transfers) | 9.6x |

| Expected change in funding per year if we decide to scale up vouchers programs in all target countries ($m) | $10.7m |

| Best guess cost-effectiveness of reallocated funding (multiples of direct cash transfers) | 17x |

| Units of value generated through reallocated funding if we decide to scale up vouchers programs in target countries (GiveWell units of value28 ) | 250,739 |

| Likelihood that funding this program will cause us to reallocate funding | |

| Expected % of total target population living in countries where governments are interested in piloting vouchers programs | 19% |

| Probability that we decide to fund pilots, conditional on government interest | 52% |

| Probability that pilots fail | 10% |

| Probability that we decide to fund scaled up vouchers programs, conditional on pilots taking place | 42% |

| Subtotal: Implied expected % of target population living in countries where we will fund scaled-up vouchers programs | 4% |

| Expected value generated | |

| Expected increase in units of value from funding this grant per year (GiveWell units of value) | 9,980 |

| How long we would fund a scaled-up vouchers program (years) | 10 |

| Present-discounted expected value of increase in units of value from funding program29 (GiveWell units of value) | 80,944 |

| Subtotal: Cost-effectiveness from funding program (multiples of direct cash transfers30 ) | 24x |

| Ad hoc adjustment for additional program benefits and downsides | -20% |

| Overall cost-effectiveness (multiples of direct cash transfers) | 19x |

5. Reservations and uncertainties

- It’s possible that this grant is duplicating work that would have happened anyway. The premise of the grant and cost-effectiveness analysis is that funding J-PAL to deliver this program could unlock opportunities to fund vouchers programs GiveWell otherwise would not have. One reason to think this may not be correct is that J-PAL has already demonstrated some government interest in vouchers, for example in Rwanda (where it recently started a pilot).31 It’s possible that this means that we would have had opportunities to fund future vouchers programs regardless of this grant. On balance, we don’t see this as substantially undermining the case for the grant (more details in footnote).32 We attempt to account for this in our cost-effectiveness analysis with a -25% adjustment, although this is a rough guess.

- We’re uncertain about J-PAL’s recommended delivery model for implementing vouchers programs. The vouchers programs that we envisage could be funded as a result of this grant are likely to be primarily delivered through existing government-run maternal and child health systems. J-PAL told us that it plans to use a light-touch technical assistance approach to support these programs, if they go ahead (e.g., one full-time member of staff per country supporting the government to design the program, manage monitoring and evaluation, and conduct other activities).33 We see this as a lighter-touch approach than the approach used in the RCTs where vouchers were successfully tested, where researchers provided more intensive support (e.g., monitoring and stipends to encourage participating shops to keep chlorine bottles in stock).34 We’d expect this to increase the risk that these programs would face substantial operational challenges.

- GiveWell has limited experience working with J-PAL. All else equal, we think grants to organizations we have not worked with before are riskier. In this case, we also understand that J-PAL is primarily a research organization, and we see J-PAL as having more limited experience of implementing programs by itself (vs. conducting research or implementing programs in collaboration with other NGOs) than typical GiveWell grantees.35

6. Plans for follow up

We will follow-up with the J-PAL team regularly (at a cadence to be determined) to get updates on this grant, and will also ask for occasional written updates. We plan to investigate opportunities to fund vouchers pilots that result from this work as and when they arise.

7. Internal forecasts

For this grant, we are recording the following forecasts, which represent the average of two GiveWell staff members’ forecasts:

| Confidence | Prediction | By time | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 65% | GiveWell will fund at least 1 vouchers pilot in a country included in this grant | July 2027 | - |

| 17.5% | … At least 2 pilots | July 2027 | - |

8. Our process

We identified this opportunity through conversations with Pascaline Dupas and subsequently other J-PAL staff. As part of our grant investigation process we conducted the following activities:

- Shared three rounds of questions with J-PAL and got written responses.

- Had several meetings with J-PAL to discuss their responses to the written questions.

- Put together the program cost-effectiveness analysis, which was reviewed internally.

9. Sources

- 1

“The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) is a global research center working to reduce poverty by ensuring that policy is informed by scientific evidence. Anchored by a network of more than 1,000 researchers at universities around the world, J-PAL conducts randomized impact evaluations to answer critical questions in the fight against poverty.” J-PAL, “About us”

- 2

“J-PAL Africa, based at the University of Cape Town, leads J-PAL’s work in sub-Saharan Africa. J-PAL Africa conducts randomized evaluations, builds partnerships for evidence-informed policymaking, and helps partners scale up effective programs.” J-PAL, “J-PAL Africa” Note that because J-PAL Africa is part of the University of Cape Town, the grant itself is to the University of Cape Town, which will receive the funds for this program.

- 3

The exact scope and delivery model for the programs we may end up funding through J-PAL is uncertain. The two studies our assessment of vouchers relies on targeted slightly different populations: (1) households with children under six years old (Dupas et al. 2023), and (2) households with 6 to 12 month old children (Dupas et al. 2016). See this section of our intervention report for details.

- 4

Note that our vouchers intervention report is dated June 2023, and our vouchers cost-effectiveness analysis is dated February 2023. We plan to update these over time as we learn more.

- 5

“...some activities we anticipate conducting by scope of work…

- Desk research: Digging into existing reports and data that speak to a country's key health statistics, current WASH infrastructure, prevalence of chlorine water treatment, government and non-governmental actors in this space, and more. We will synthesize these learnings into written reports and/or slide decks to help us gauge viability of the program and possible next steps.

- Relationship building: Conduct an in depth stakeholder mapping to identify key actors in this space in each country of interest. Once this is done, start to actively build relationships to generate buy-in for scaling chlorine coupons in these settings.

- Travel: Once we have identified a country as promising based on the desk research and initial partner outreach, we plan to conduct scoping trips to the countries to take these conversations forward. During these visits, we will meet with as many actors in the MCH space as possible, visit local health centers, identify potential research partners who could conduct the pilots, share evidence on the program, and map initial opportunities for designing a voucher program in the new context.”

J-PAL Africa, Q&A document for chlorine vouchers project (unpublished)

- 6

Water, sanitation, and hygiene.

- 7

“Pascaline will be the academic lead of this project, engaging in conversations with our government counterparts and working closely with J-PAL staff to think through pilot design considerations, monitoring and evaluation plans, and more.” J-PAL Africa, Q&A document for chlorine vouchers project (unpublished)

- 8

“Pascaline Dupas is a Professor of Economics and Public Affairs at Princeton University and Co-Scientific Director of J-PAL Africa.” J-PAL, “Pascaline Dupas”

- 9

Elisa Maffioli is an Assistant Professor of Health Management and Policy and of Global Public Health at the University of Michigan School of Public Health.

- 10

Note: we have since updated this list based on more up-to-date estimates of the health burden in each country, and at the time of writing (February 2025) plan to focus the grant activities on a subset of 13 of these countries (the list below, but excluding Burundi and Guinea-Bissau).

- 11

Chad, Niger, Central African Republic, Mali, Burkina Faso, South Sudan, Somalia, Togo, Burundi, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Cameroon, Madagascar, Guinea-Bissau, and Benin. See list here.

- 12

Enteric infections are infections of the intestine, which we expect cause a substantial share of the mortality that could be averted by chlorination programs. More in our report on water quality interventions here.

Definition from the Institute of Health Metrics and Education (IHME): “This aggregate cause incorporates deaths and disabilities resulting from infections to the intestines caused by a variety of different aetiologies including diarrhoeal diseases, typhoid and paratyphoid, and invasive nontyphoidal salmonella (iNTS).” - 13

See how we calculated these cost-effectiveness estimates here. These estimates are derived from our February 2023 rough cost-effectiveness estimates, which we've adjusted by the same factor by which our Liberia estimate changed between Feb 2023 and May 2024 (our May 2024 internal CEA only focused on Liberia). We excluded Nigeria from the scope of this grant even though we see it as a high priority location because at the time we made the grant decision we were also considering a separate pilot of chlorine vouchers in Nigeria, implemented by a different NGO (Evidence Action). Our 2023 safe water scoping grant to Evidence Action supported scoping work in Nigeria.

- 14

“Two full time PMs for 18 months” Source: J-PAL, Budget Proposal November 2024 (10% Overhead Adjustment), (unpublished)

- 15

Source: J-PAL, Budget Proposal November 2024 (10% Overhead Adjustment) (unpublished)

Note that the total budget for the grant was $506,893 at the point we made our grant decision. Between the point we made the grant decision and the time of writing, J-PAL reduced its budget to $472,362 in order to adhere to GiveWell’s 10% indirect cost cap for universities. - 16

See the GiveWell water team research strategy, published June 2024.

- 17

See this section of our vouchers intervention report. The RCTs are Dupas et al. 2023 and Dupas et al. 2016

- 18

See this section of our vouchers intervention report for more details.

- 19

See this section of our vouchers intervention report for more analysis of what we’d expect to be the main barriers to scaling vouchers programs.

- 20

- 21

“The Government of Rwanda (GoR) has expressed interest in developing, testing, and scaling a program fully subsidizing water treatment for households with young children, in rural areas where people access untreated water from wells or springs.” J-PAL, Integrating water treatment into maternal and child health services: concept note, May 2024 (unpublished).

In a call in August 2024, J-PAL staff informed us that this work was likely to go ahead. Source: GiveWell's conversation with J-PAL, August 7th, 2024 (unpublished). - 22

This understanding is based on conversations with J-PAL and on J-PAL, Integrating water treatment into maternal and child health services: concept note, May 2024 (unpublished).

- 23

This understanding is based on conversations with J-PAL during our grant investigation for this work.s.

- 24

Source: conversation with Evidence Action staff, August 22nd, 2024 (unpublished).

- 25

This benchmark is based on "moral weights," a system we use to quantify the benefits of different impacts (e.g. increased income vs reduced deaths). We benchmark to a value of 1, which we define as the value of doubling someone’s consumption for one year. Our estimate of the value of direct cash transfers is 0.00335 per dollar. For more on how we use moral weights, see this document.

Note: This estimate of the value per dollar donated to cash transfers is out of date as of 2024. We are continuing to use this outdated estimate for now to preserve our ability to compare across programs, while we reevaluate the benchmark we want to use to measure and communicate cost-effectiveness.

For more on our update on the impact of unconditional cash transfers, see this page. - 26

This breaks down into the following (all rough estimates):

- Initial grant success: We estimate 19% of the reachable population in the target countries live in places whose governments will be interested in pilots.

- Probability that we decide to fund pilots, conditional on government interest: We estimate a 52% chance that we’ll decide to fund these pilots.

- Probability that pilots fail (e.g., because of civil war, natural disaster, etc.): 10%

- Probability that we decide to fund scaled up vouchers programs, conditional on pilots taking place: 42%

(19% x 52% x (100% - 10%) x 42%)) = 4%. See calculations and assumptions here.

- 27

See our full cost-effectiveness analysis here.

- Scoping/stakeholder engagement costs (~$0.47m): This is based on the unpublished budget J-PAL shared with us.

- Pilot costs: We estimate these based on a rough estimate of $350k per pilot (including staff time) per country that’s interested in delivering a pilot, and guesses about the total number of pilots we’re likely to fund (see here in our CEA, and supplementary calculations here).

- Cost-effectiveness of counterfactual opportunities: We use GiveWell’s standard approach of using 3 scenarios for what will happen to our future cost-effectiveness bar (10x, 8x, 12x), weighted by the likelihood of each scenario. (see here)

- Likelihood of government interest in vouchers (19%): We estimate the likelihood that governments will be interested in piloting vouchers, based on various possible scenarios to which we assign rough, subjective probabilities. See here in our CEA, and supplementary calculations here.

- Probability that we decide to fund pilots (40% - 60%): This is an estimate of the likelihood that GiveWell will fund a pilot if there is government interest. The higher our funding bar, the less likely we are to be interested in funding pilots (because the bar they’d need to meet will be higher). See here in our CEA.

- Probability that pilots fail (10%): This is a rough estimate of the probability that we fund a pilot and it fails (e.g. due to natural disaster, political instability, etc.). See here in our CEA.

- Probability that we decide to fund scaled up vouchers programs, conditional on pilots taking place (30% - 50%): this is an estimate of the likelihood that GiveWell will choose to scale vouchers programs in locations where we have previously funded pilots. The higher our funding bar, the less likely we are to be interested in funding scale-up. See here in our CEA

- Change in funding to program per year if we decide to scale up the program (~$11m, see here in our CEA): This represents the total annual funding GiveWell could plausibly direct to chlorine vouchers programs in focus countries if this grant successfully unlocked opportunities to fund vouchers programs in those countries. This is based on rough calculations from our analysis of the total possible room for more funding for scaled-up vouchers programs from our chlorine vouchers intervention report (source). For this grant we made two changes to our earlier calculations:

- We added a 40% (i.e. -60%) adjustment for time to scale-up, i.e. if we did scale up a vouchers program it would take a long time, and so we shouldn’t count the full benefits over the full 10 year window.

- We reduced the target population that we estimate will be reachable through the program from 45% of each country’s rural population (based on a guess) to 33%, based on unpublished calculations we have received from Evidence Action the proportion of households it estimates could be reachable through a vouchers program in Liberia. This corresponds to the proportion of households that have an expectant parent, child under age 1, or child under age 5 that has visited a health facility in the previous year.

- Estimated cost-effectiveness of this reallocated funding (17x): This is our rough cost-effectiveness estimate for delivering an at-scale vouchers program in each country, weighted by the size of the target population in each country. See here in our CEA. This includes a rough -10% adjustment accounting for a guess that countries with higher mortality burden are also harder to implement in.

- This is based on roughly extrapolating our cost-effectiveness estimate from our February 2023 vouchers cost-effectiveness analysis (focused on a subgroup of countries that rank low on the socio-demographic index) to other countries based on the level of under-five mortality and the % of mortality from enteric infection in each location. See calculations here.

- We roughly adjust these estimates down by ~20% (calculations here). This adjustment corresponds to the gap between our most recent (May 2024) internal cost-effectiveness analysis for a vouchers program in Liberia (best estimate of 9x cash transfers) and the estimate for Liberia in the earlier extrapolated calculations of 11x cash transfers. We apply this ratio to all other countries to come up with our updated best guess.

- 28

This is an arbitrary unit we use to compare the moral value of different kinds of outcomes (e.g., increased income vs reduced deaths). We benchmark to a value of 1, which we define as the value of doubling someone’s consumption for one year. More here.

- 29

This calculation uses a 4% discount rate (i.e. a percentage rate by which you discount future costs or benefits). More on our approach to discounting here.

- 30

0.003355 refers to the number of units of value generated per dollar spent on direct cash transfers. See this cost-effectiveness analysis for our calculations.

Note: This estimate of the value per dollar donated to cash transfers is out of date as of 2024. We are continuing to use this outdated estimate for now to preserve our ability to compare across programs, while we reevaluate the benchmark we want to use to measure and communicate cost-effectiveness.

For more on our update on the impact of unconditional cash transfers, see this page - 31

More above.

- 32

While we think the dynamic described above probably does attenuate the benefits of funding a scoping-only grant to some extent, we still think the grant could have benefits through the following channels:

- Creating opportunities in high burden countries that wouldn't have been possible otherwise, e.g., because J-PAL doesn’t have existing relationships in those countries, or because of capacity constraints.

- Speeding up opportunities to fund programs in high burden countries that may have come around at some point in the future in any case.

- 33

“At the core of our model, we want to work within existing maternal and child health care systems, not to set up a new system to implement this work ourselves. As such, we hypothesize that having one full-time staff member in a country to support the government (or other MCH actors) to pilot and scale the program will provide enough technical assistance and momentum to get the work started, while ensuring we work within existing, sustainable and scalable structures from the beginning.” J-PAL Africa, Q&A document for chlorine vouchers project, (unpublished).

- 34

For more details, see this section of our chlorine vouchers intervention report.

- 35

This understanding is based on conversations with J-PAL and unpublished examples J-PAL shared of its previous work with GiveWell.