We have published a more recent review of this organization. See our most recent report on the SCI Foundation, formerly known as the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative.

We consider SCI an "organization to watch." We will continue to follow SCI's progress and may recommend it in the future.

Table of Contents

Summary

The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI) assists African governments with treatment of neglected tropical diseases and runs a number of smaller-scale projects (more).

We feel that SCI is remarkable for its (a) focus on a program with a strong track record and excellent cost-effectiveness; (b) demonstrated results - the research we have seen suggests that programs SCI has been involved with have been successful in reducing the prevalence of infection (more).

However, we cannot confidently recommend SCI without addressing the following issues:

- Financials. We have seen financial reporting for only a portion of SCI's activities; we would need to see a full accounting of its expenses in order to give a recommendation.

- Concerns about evidence of effectiveness. While studies have implied success in reducing the prevalence of infection, we are concerned about (a) how relevant the studied populations are to the full populations treated by the programs; (b) whether successful treatment has been sustained after the study periods. In addition, we have had trouble getting strong information on the relationship between infections and quality of life. Official estimates imply that deworming is highly cost-effective in terms of changes in quality of life, but we have questions about the conditions under which these estimates are applicable, and our investigation of these matters is ongoing.

- Use of smaller donations. SCI has told us that it has only recently begun to manage and use donations from individuals. SCI solicits institutional funders for its large-scale, country-level projects, and uses non-institutional funding for smaller projects. The smaller projects are significantly different in scope from the work that has yielded positive results in the past, and we seek more information about the costs and effectiveness of these projects.

SCI does not currently qualify for our highest ratings, but we plan on continuing to follow SCI's work closely, and we may recommend it in the future.

What do they do?

SCI was founded in 2002 and funded via grants from the Gates Foundation, USAID, and Geneva Global,1 and initially treated two diseases: schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths.2 Over the course of its history, SCI focused on administering these grants. In 2009-2010, as the grants from the Gates Foundation and USAID were expiring, SCI began to look for new sources of funding for programs that treated a larger number of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).3 Thus present and future activities may differ from past activities in two ways: (a) source and conditions of funding; and (b) specifics of how the programs are implemented due to a change in the diseases targeted.

SCI has two prospective streams of funding:

- Large-scale, country-level programs supported by government or institutional donors

- Smaller-scale projects supported by individual donors

We discuss each below.

Large-scale programs

SCI provides technical assistance and funding to countries in sub-Saharan Africa to implement mass drug administrations of medications that prevent or treat neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).4 SCI works to control or eliminate seven NTDs: three types of soil-transmitted helminths, lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, and trachoma.5

SCI recently received a grant to implement a large-scale program in Côte d'Ivoire,6 and continues to solicit large funders for projects in Mozambique and Malawi.7

Spending breakdown

SCI provided us with unaudited financial data for 2002-2010. These documents cover a relatively small portion of SCI's activities;8 it is unclear to us how this particular portion was selected to be shared with us; and, therefore it is not a full picture of how SCI spends its money.

With these limitations in mind, SCI's expenditures were 59% country programs, 28% drug procurement, 9% salaries, and 5% "OHD/College contribution." SCI provided more detail on what the money was spent on for a portion of these funds allocated to specific grant-funded projects. 48% of the funding for which we have more detail was granted to African governments,9 26% was spent on "lab and works supplies," 12% directly on staff, 6% on "overheads," 2% on postage, 2% on travel, 1% on "subsistence," 1% on equipment and hardware purchase, and the remainder on 20 additional line items.10

From conversations with Alan Fenwick, director of SCI, and a grant proposal submitted by SCI to the funding agency USAID, it appears that SCI's role in mass drug administrations is to:11

- Assist with planning and fund raising.

- Deliver funding and drugs to governments.

- Advocate for the benefits of mass drug distributions among children and high risk groups, local leaders and government officials, and teachers and healthcare workers.

- Provide financial management and technical support.

- Develop procedures for monitoring and evaluation.

Small-scale programs

SCI has also worked on a number of smaller projects and has told us that donations from individual donors are used for projects such as these. Examples of past projects:12

- A small treatment project in Cote d'Ivoire that will be scaled up with a grant from the U.K. Department for International Development.

- A program run by a doctor in Mozambique to test and treat 70,000 people in Mozambique.

- A surgery program in Niger for patients with hydrocele, a symptom of lymphatic filariasis.

- A treatment program for residents of Ugandan islands in Lake Victoria.

SCI told us in February 2011 that it had set up a way to receive donations from individuals less than a year before and thus did not yet have audited financial data from the account holding such donations.13

Does it work?

Independent evidence of program effectiveness

The effectiveness of mass drug administration programs for controlling onchocerciasis, soil-transmitted helminths, and schistosomiasis and for eliminating lymphatic filariasis is well-supported by available evidence. The SAFE strategy is also likely effective, although some components of the strategy are better-established than others. For details, see:

- Our review of mass drug administration to control schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths

- Our review of mass drug administration to eliminate lymphatic filariasis

- Our review of mass drug administration to control onchocerciasis

- Our review of the SAFE strategy to control trachoma

Internal monitoring: large-scale programs

We have seen two technical reports, and summaries of several other evaluations, showing substantial drops in the prevalence of infections after SCI's involvement. The drops in prevalence are substantial enough that we think crediting SCI for them is reasonable (details below). That said, it is not fully clear to us (a) how relevant the studied populations are to the full populations treated by the programs; (b) whether successful treatment has been sustained after the study periods; (c) how these drops in prevalence of infection translate to lives changed for the better; (d) how past successful activities relate to future activities.

Evidence regarding drops in prevalence of infection

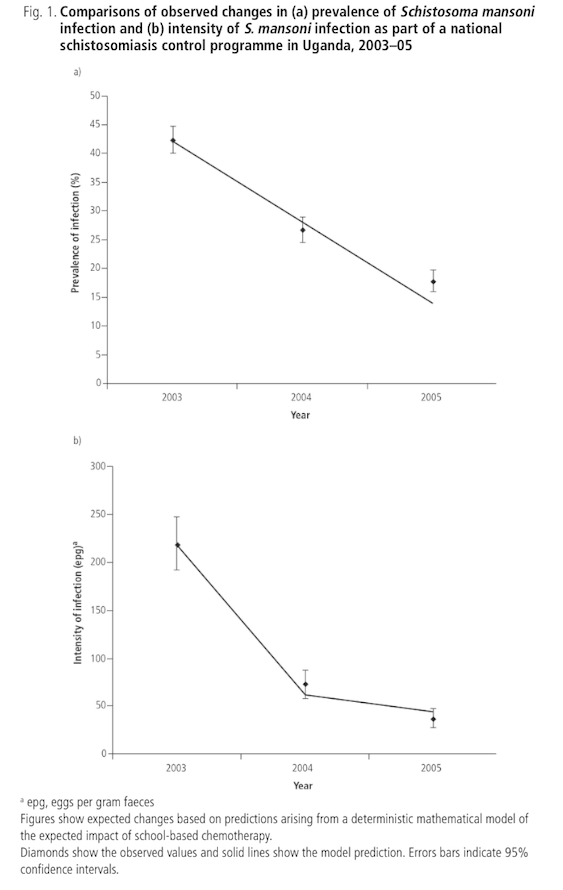

- Uganda: SCI began working in Uganda in 2003.14

A study of 1871 schoolchildren15

found that prevalence of intestinal schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths and anemia decreased significantly after 2003.16

It is not clear to us whether the sample of studied schoolchildren was representative of the project population as a whole. The sample was drawn from districts "selected to represent transmission settings ... Within each district, schools were stratified according to ... infection prevalence: two with high prevalence (> 50%), two with medium prevalence (10–49%) and one with low prevalence ( 10%)."17 This would appear to ensure, for example, that 1/3 of the sample came from high-prevalence schools, even though it wasn't necessarily the case that 1/3 of all schools in the program were high prevalence.

The study had a low follow-up rate, with only 43.3% of children originally selected for inclusion surveyed in all three surveys.18

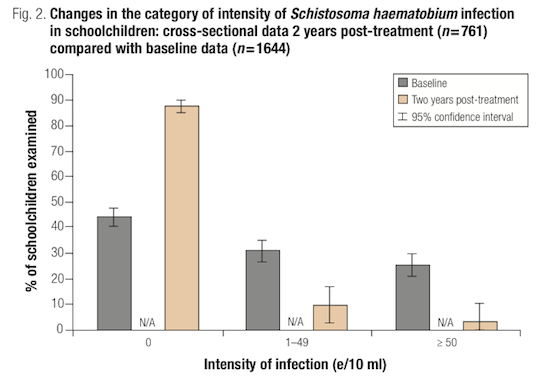

- Burkina Faso: SCI began working in Burkina Faso in 2004.19

Beginning in that year, a sample of school-aged children was examined for two types of schistosomiasis before treatment, one year following treatment, and two years following treatment.20

44% of children selected for the baseline survey were successfully followed up in years one and two, but valid data for all three years for one type of schistosomiasis, S. haematobium, was only available for 44% or those originally selected (and was only available for 19% for another type of schistosomiasis, S. mansoni).21

Among those sampled, prevalence of S. haematobium infection fell (from 60% at baseline to 8% in year two)22

and intensity significantly decreased (from 94 eggs per 10 ml of urine at baseline to 7 in year two).23

Overall prevalence and intensity of S. mansoni were low at baseline. They decreased significantly at year two, but not at year one.24

A cross-sectional sample of children from the same schools was surveyed in year two,25 which also showed significant decreases in urinary schistosomiasis prevalence (from 56% at baseline to 13% in year two)26 and intensity.27

SCI's website presents data from Burkina Faso for year three, as well as for prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths and anemia.28 We have not be able to find the source report for this data.29

As with the above study, we have concerns about representativeness, as the sample of schoolchildren was drawn from "four priority regions targeted in 2004," and not necessarily from the program area as a whole.30

- Niger: SCI began working in Niger in 2004.31

Schoolchildren aged 7, 8, and 11 from selected villages in two regions of Niger32

were examined for urinary schistosomiasis in 2004, one year post-treatment and again in year two.33

89% of those surveyed at baseline were found for follow up in year one.34

Although the results of the study indicate decreases in schistosomiasis prevalence and infection intensity, the data from this study is presented as "paired analysis," and it unclear to us how this corresponds to overall changes in prevalence and intensity.35

SCI's website presents data from Niger for three follow-up years, showing that gains were maintained over time.36 We have not seen the technical reports on how this data was collected.37

As with the above two studies, we have concerns about representativeness because "villages ... were randomly selected to represent the two main transmission patterns in Niger: six villages located near permanent (Tabalak, Kokorou) or semi-permanent (Kaou, Mozague, Rouafi, and Sabon Birni) ponds and two (Saga Fondo, Sanguile) located along the Niger River."38 While this may have been the best way to represent the main transmission patterns, it is unclear to us whether such villages would be representative of the project population as a whole.

- Mali: SCI began working in Mali in 2004.39 SCI's website describes baseline (2004), year one (2005-2006), and year two (2006-2007) surveys of 1511 Malian children (58% of those interviewed at baseline), which found significant decreases in schistosomiasis hookworm prevalence among those surveyed.40 We have not been able to find details of how the children were selected for the survey or whether gains persisted after year two.41 SCI told us that it has handed over its Mali operations to the NGO Helen Keller International.42

- Tanzania: SCI's website describes baseline (2005) and year one surveys of 2044 Tanzanian children (65% of those interviewed at baseline), which found significant decreases in schistosomiasis infection, hookworm infection, and anemia among those surveyed.43 We have not been able to find details of how the children were selected for the survey or whether gains persisted after year one.44

- Zambia: SCI encountered difficulties in accomplishing its treatment targets in Zambia. An article by the director of SCI and others states:45

Zambia has been less successful in reaching its original programme target of expanding coverage to treating 2 million school-aged individuals and had only achieved, according to incompletely reported coverage, around 25% of this target by July 2007, which might be partially explained by difficulties in obtaining reliable treatment data from the field...The training of CDDs [Community Drug Distributors] and teachers in rural areas turned out to be significantly more expensive than in other SCI-supported countries...The SCI exited by handing over the programme to the MoH in the hope that they would continue to support the SHN programme, however at the time whether the treatment strategy was to continue was dependent on internal and external funding and the appointment of a full-time national co-ordinator in the Zambian government (in the opinion of the authors).

We have not seen monitoring data from Zambia.

- Burundi: As of September 2010, SCI stated on its website that baseline and two years of follow up data had been collected in Burundi, but that the data had not yet been fully analyzed.46

- Rwanda: As of September 2010, SCI stated on its website that monitoring and evaluation data had been collected in Rwanda, but that the data had not yet been fully analyzed.47

Concerns about the above evidence

- Relevance of studied populations to the full populations treated by the programs. As discussed above, the studies we've seen appear to have focused on high-transmission areas, and it is unclear to us how representative their areas of focus are of the overall program target populations. In addition, follow up rates tended to be quite low (38-57% attrition over the two years of study).48 If healthier participants were easier to follow up with than sicker participants, than the effect of the treatment will be overestimated.

- Concerns over whether treatment was sustained. SCI reports that it collected monitoring data for some countries for years after the studies we have found ended (up to four years after baseline in Uganda and Niger, for example), but we have not seen this data.49

- Relationship between infection prevalence and lives changed for the better. We have had trouble getting strong information on the relationship between infections and quality of life. Official estimates imply that deworming is highly cost-effective in terms of changes in quality of life, but we have questions about the conditions under which these estimates are applicable, and our investigation of these matters is ongoing.

- Relationship between past, successful activities and future activities.The above data is from programs that delivered drugs for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths. Since 2006, SCI has expanded its focus to include drugs and other interventions for an additional three NTDs.50

SCI told us, "Our current methodology is based on what we did for the first 6 years, but we have a flexible approach and each country runs its own country programme and we are there to advise and assist...The integration of NTD control is still pretty much based on the first 6 years work."51

SCI told us that it monitors program implementation and disease rates in the countries it supports.52 We requested reports from this process, but have not received them.

Internal monitoring: small-scale programs

We have not seen monitoring or evaluation reports from SCI's small-scale programs such as Cote d'Ivoire, Mozambique, the surgery program in Niger, or Ugandan islands in Lake Victoria. These programs may account for a small proportion of SCI's overall budget, but SCI told us that they are the primary use of donations from individuals.53

Possible negative and offsetting impact

- Replacement of government funding: In the past, SCI has largely supported programs that did not exist before its support.54 This also appears to be the case for the one not-yet-funded proposal we have seen.55 We have not seen data on government spending on NTDs before and after receiving SCI support.

- Diversion of skilled labor: Drug distribution occurs only once or twice per year and appears to be conducted by teachers, community drug distributors (who receive minimal training to fulfill this role), and health center staff.56 Given the limited time and skill demands of mass drug distribution and the fact that NTD control appears to be one of the most effective and cost-effective medical interventions,57 we are not highly concerned about distorted incentives for skilled professionals.

What do you get for your dollar?

The Disease Control Priorities report estimates that mass drug distribution programs to fight schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, lymphatic filariasis, and onchocerciasis are among the most cost-effective programs known, costing between $4 and $40 per disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) saved.58

Note: In September 2011, we confirmed a number of errors in the estimates for the cost-effectiveness of deworming published in the Disease Control Priorities report. Based on those findings, we are currently rethinking our use of cost-effectiveness estimates, like the DCP2's, for which the full details of the calculations are not public. For more information, see our blog post on the topic.

SCI states that it "needs as little as 25 pence/50¢ per person per year, to facilitate delivery of treatments in Africa."59 We are currently (March 2011) analyzing these cost-effectiveness figures to better understand them and the assumptions they require.

We remain unsure whether small to medium donations to SCI, which are unlikely to fund large-scale programs like those studied by the Disease Control Priorities report, would have similar cost-effectiveness.

Room for more funds?

SCI told us that how it would use additional unrestricted funding is dependent on the size of the donation received. It currently uses the smaller donations it receives ($100,000 per year) to fund small projects in Cote d’Ivoire and Mozambique and could use up to an additional $100,000 for these programs. If it received a larger amount, SCI "would start a larger scale campaign in a selected country and would need staff time and travel to oversee the larger piece of work."60

SCI also told us that additional donations might be used for research, some additional travel by SCI staff members, and microscopes.61

SCI also told us that it could use up to $50 million in 2011, and that it currently expects to receive a maximum of $20 million for that year. We believe that it is likely that SCI could productively use additional funds in 2011, though we remain unsure of the size of the funding gap because we have not seen details of how much in additional funding could be used for each activity.

Sources

- Fenwick, Alan, et al. 2009. The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI): Rationale, development and implementation from 2002–2008. Parasitology 136: 1719-1730. Summary available at http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&ai… (accessed September 9, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5sbwCb0Ht.

- Fenwick, Alan. SCI Director. Email to GiveWell, August 10, 2010.

- Fenwick, Alan. SCI Director. Email to GiveWell, February 1, 2011.

- Fenwick, Alan. SCI Director. Phone conversation with GiveWell, July 2009.

- Fenwick, Alan. SCI Director. Phone conversation with GiveWell, June 17, 2010.

- Fenwick, Alan. SCI Director. Phone conversation with GiveWell, February 16, 2011.

- GiveWell. Interpreting the disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) metric.

- GiveWell. Mass drug administration to control onchocerciasis.

- GiveWell. Mass drug administration to control schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths.

- GiveWell. Mass drug administration to eliminate lymphatic filariasis.

- GiveWell. SAFE strategy to control trachoma.

- Kabatereine, Narcis B., et al. 2007. Impact of a national helminth control programme on infection and morbidity in Ugandan schoolchildren. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 85: 91-99.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Board management accounts (April 2010). SCI asked us not to publish this document.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Burkina Faso: Impact. http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/schisto/wherewework/burkinafaso/burkinafasoi… (accessed September 9, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5sc48n1yv.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Burundi: Impact. http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/schisto/wherewework/burundi/burundiimpact (accessed September 9, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5scR0RjN3.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Burundi: Strategy. http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/schisto/wherewework/burundi/burundistrategy (accessed September 9, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5scPivJhr.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Mali: Impact. http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/schisto/wherewework/mali/maliimpact (accessed September 9, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5scPHop3a.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Neglected tropical diseases in Mozambique. SCI asked that we keep this document confidential.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Niger: Impact. http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/schisto/wherewework/niger/nigerimpact (accessed September 16, 2010. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5smNthzdi.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Proposal by SCI, Imperial College to manage the Program for Integrated Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Côte d'Ivoire. SCI asked that we keep this document confidential.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Rwanda: Impact. http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/schisto/wherewework/rwanda/rwandaimpact (accessed September 9, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5scQwHDti.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Rwanda: Strategy. http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/schisto/wherewework/rwanda/rwandastrategy (accessed September 9, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5scPnJJIY.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Summary sheet of treatments instigated and overseen by SCI. SCI asked that we keep this document confidential.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. Tanzania: Impact. http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/schisto/wherewework/tanzania/tanzaniaimpact (accessed September 9, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5sbwJEGqB.

- Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. What we do. http://www3.imperial.ac.uk/schisto/whatwedo (accessed September 10, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5sdLNO10H.

- Tohon, Zilahatou B., et al. 2008. Controlling schistosomiasis: Significant decrease of anaemia prevalence one year after a single dose of praziquantel in Nigerien schoolchildren (PDF). PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2: e241.

- Touré, Seydou, et al. 2008. Two-year impact of single praziquantel treatment on infection in the national control programme on schistosomiasis in Burkina Faso (PDF). Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86: 780–787.

- 1

"In 2002 the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s Global Health Programme granted a £20 million award to establish the SCI at Imperial College London...The American people, through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), are now supporting SCI and others to further integrated NTD control in eight countries, while Geneva Global (an international philanthropy company) is funding SCI to promote integrated NTD control in Rwanda and Burundi." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "About Us."

- 2

"The move towards national control programmes in sub-Saharan Africa was facilitated by an award from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Global Health Program in 2002, to the SCI for the implementation and evaluation of control of schistosomiasis...One of the SCI’s first actions was to adopt integration of intestinal worm control. Whereas the SCI was initially established to target a single disease (i.e. schistosomiasis using PZQ), it was very soon realized that wherever there is schistosomiasis, co-infections with soil-transmitted helminths (STHs) such as Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura and hook- worm are the norm rather than the exception (Geiger, 2008)...Thus the SCI decided from the outset to offer treatment for STH infections together with schistosomiasis." Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 2.

- 3

- "We started off before anyone was treating neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). We had a single donor and for 4 yrs had no other grants. As a result of what we did, we attracted more money: from Gates, USAID, and Geneva Global. We moved forward from a single donor and a single disease to multiple NTDs and multiple donors. At that time, I tried to find other donors to build our portfolio but it was during the financial crisis. 12 months ago, we were in difficult waters. The award of DfID grant was very important to us because in the next year, Gates and USAID funding will stop. Private donations and a massive World Bank grant for Yemen has come in." Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, February 16, 2011.

- "As of 2009 however, schistosomiasis and STH are no longer considered in isolation...SCI and partners are now continually striving to raise further funds to expand the coverage of integrated control of NTDs in sub-Saharan Africa." Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 10.

- 4

"In order to realise this aim the SCI assists Ministries of Health in sub-Saharan African countries to develop and expand their existing NTD control programmes into successful National NTD Control Programmes. Furthermore, by presenting an integrated approach to mass drug administration, (simultaneously tackling 7 NTDs), the Ministries of Health have an affordable and realistic means available by which to achieve their goal to reduce the prevalence of these diseases in their populace to a level where they no longer represent a public health burden." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "What We Do."

Between 2003 and 2008, SCI provided treatment for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths to the following number of people (Fenwick, et al. 2009, Pg 3, Table 1).

Number treated by country (millions) Year Uganda Burkina Faso Niger Mali Tanzania Zambia 2003 0.43 - - - 0.10 - 2004 1.23 1.03 0.67 - 0.44 - 2005 2.99 2.30 2.01 2.60 2.95 - 2006 1.51 2.82 1.56 2.18 0.38 0.56 2007 1.81 0.75 2.07 0.65 2.65 0.25 2008 1.50 2.70 5.28 - 1.24 - SCI began targeting additional NTDs from 2008 on: "A revised exit strategy for each country involved the schistosomiasis and STH control programmes being absorbed into a more holistic countrywide NTD integrated control package. This means schistoso- miasis and STH control programmes could and should be integrated with onchocerciasis and lym- phatic filariasis control which requires annual doses of ivermectin (Mectizan1) and ALB. Then, where trachoma is also endemic, annual azithromycin (Zithromax1) treatments could and should be added into an integrated NTD control programme." Fenwick, et al. 2009, Pg 9.

Since 2007, SCI has also worked in Rwanda and Burundi (see Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Burundi: Strategy," and Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Rwanda: Strategy").

Note that, in addition to mass drug administration, SCI's NTD control efforts may include vector control (of mosquitoes to control lymphatic filariasis), health education, sanitation and water interventions, and surgery. (Sources: Scistosomiasis Control Initiative. "Proposal by SCI, Imperial College to manage the Program for Integrated Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Côte d'Ivoire," and Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Neglected Tropical Diseases in Mozambique.")

- 5

"The SCI aims to control or eliminate the seven most prevalent NTDs (soil-transmitted helminths (STH-ascariasis, hookworm infection, trichuriasis), lymphatic filariasis (LF), onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, and trachoma) from sub-Saharan Africa." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "What We Do."

- 6

"In Cote d'Ivore, we now we have funding from the U.K. Department for International Development (DfID). There will eventually be a national program." Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, February 16, 2011.

- 7

"For the smaller donor, we have two or three projects, which we have been supporting and which will hopefully lead to pilot project [for a national program] in their respective countries...In Mozambique, we have a doctor running a practice for 70,000 people. We have been funding her to test people, do surveys and give drugs to treat people...

In Malawi, we drew up a plan for 5 years. We used unrestricted money to fund the planning, and we reckon that we'll need $20 million over next 6 years to implement the plan. DfID has given us money to start the program, and a couple other donors—some through the Global Network and one high net worth individual in the UK who's shown an interest. Another government department has also shown interest." Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, February 16, 2011. - 8

The amount accounted for totals 14 million, but it is not clear what currency this is in (we would guess either U.S. dollars or British Pounds). SCI spent a total of $68,246,054 in 2002-April 2010.

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Board Management Accounts (April 2010)." - 9

"Just to let you know that the line "external consultants" which seems a high personnel cost in some sub awards is in fact a transfer to the Countries - which for the sake of Imperial accounting are classed as 'external consultants because Imperial College accounting system has no line for field work in Africa." Alan Fenwick, email to GiveWell, February 1, 2011.

- 10

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Board Management Accounts (April 2010)."

- 11

- Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, June 17, 2010.

- Scistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Summary Sheet of Treatments Instigated and Overseen by SCI."

- Scistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Proposal by SCI, Imperial College to Manage the Program for Integrated Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Côte d'Ivoire."

- 12

"For the smaller donor, we have two or three projects, which we have been supporting and which will hopefully lead to pilot project in their respective countries.

1. In Cote d'Ivore, we now we have funding from the U.K. Department for International Development (DfID). There will eventually be a national program.

2. In Mozambique, we have a doctor running a practice for 70,000 people. We have been funding her to test people, do surveys and give drugs to treat people. Up until now, that has taken all the individual funding that comes in.

Once we have people that want to give at least $100,000, we talk to them directly. Two examples:

1. Someone wanted to do something special with his money, so we're doing hydrocele surgery in Niger. He gave us $200,000 and we told him we could do ~1000 hydrocele surgeries.

2. Another person was interested in Uganda. So, we identified islands there in Lake Victoria that are relatively accessible and provided treatments there."

Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, February 16, 2011. - 13

"GiveWell: It's important to us to have a full financial picture, preferably audited, of an organization. Can we see full/audited financial information?

SCI: We don't consolidate the different donations from different donors into one account. That's because we report separately to different donors what we do with their funding. We don't have overall audited financials. Each audit is done by each donor. We report to a board and show each audited account for each donor. We don't put it one pool.

GiveWell: Has the account with money from individuals been audited?

SCI: Those haven't come in over a full year yet, but we will audit them at the end of the financial year, which happens at the end of March. Only recently have we brought individual donations in."

Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, February 16, 2011. - 14

"Uganda was the first country which launched a SCI-supported control programme in April 2003." Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 3.

- 15

"The districts were selected to represent different transmission settings: Arua, Moyo and Nebbi, along the Albert Nile; Hoima and Masindi along Lake Albert; and Bugiri, Busia and Mayuge along Lake Victoria. Within each district, schools were strati- fied according to S. mansoni infection prevalence: two with high prevalence (> 50%), two with medium prevalence (10–49%) and one with low prevalence ( 10%). In each school, 30 children (15 males and 15 females) were randomly selected from four age groups: six, seven, eight and eleven years, yielding 120 children. Twelve and 24 months later, we re-visited the schools and re-examined the same children if they could be traced. We undertook evaluation surveys every year during February–March in the Lake Victoria area, March–April in Lake Albert area, and October–November in the Albert Nile." Kabatereine et al. 2007, Pg 92.

- 16

From Kabatereine et al. 2007, Pg 93, Table 2.

2003 (baseline) 2004 (year one follow up) 2005 (year two follow up) % infected with schistosomiasis 42% 27% 18% % infected with hookworm 51% 24% 11% % infected with Ascaris lumbricodes 3% 2% 1% % infected with Trichuris trichiura 2% 3% 2% Mean schistosomiasis intensity 220 73 37 Mean hookworm intensity 309 77 22 % anemic 52% 46% 32% - 17

"The districts were selected to represent different transmission settings: Arua, Moyo and Nebbi, along the Albert Nile; Hoima and Masindi along Lake Albert; and Bugiri, Busia and Mayuge along Lake Victoria. Within each district, schools were stratified according to S. mansoni infection prevalence: two with high prevalence (> 50%), two with medium prevalence (10–49%) and one with low prevalence ( 10%). In each school, 30 children (15 males and 15 females) were randomly selected from four age groups: six, seven, eight and eleven years, yielding 120 children. Twelve and 24 months later, we re-visited the schools and re-examined the same children if they could be traced. We undertook evaluation surveys every year during February–March in the Lake Victoria area, March–April in Lake Albert area, and October–November in the Albert Nile." Kabatereine et al. 2007, Pg 92.

- 18

"We enrolled 4351 children from 37 schools, of which 2815 (64.7%) were traced and treated at one year follow-up and 1871 (43.0%) at two year follow- up. The baseline characteristics did not differ significantly among those included in the evaluation one-year post treatment and those lost to follow-up (see Table 1, available at http://www.who.int). However, we found the prevalence and mean intensity of S. mansoni to be significantly higher among those children who were lost to follow-up compared to those successfully followed up two years post treatment." Kabatereine et al. 2007, Pgs 93-94.

- 19

"The first treatment with PZQ and ALB was implemented during 2004 and 2005 in a staggered two-phased campaign." Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 5.

- 20

"We now report the impact of biennial treatment strategy on urinary schistosomiasis through both school- and community-based drug deliveries for school-age children in Burkina Faso in western Africa...Sentinel schools were randomly selected from all schools in four priority regions targeted in 2004. Within each school, 180 children were selected randomly from each of the 7-, 8- and 11-year- old groups with approximately equal numbers of boys and girls in each age group. However, due to number and gender restrictions in each age group in each school, the actual age range was expanded to 6–14 years. Where the total number was not met in one school, the closest school with the same ecological conditions was selected. As a result, a cohort of 1727 schoolchildren was randomly selected at baseline from 16 schools. The cohort children were examined at baseline and followed up 1 year post-treatment (in 2005) and 2 years post-treatment (in 2006)...One urine specimen was collected from each child to determine S. haematobium infection using the filtration method and microscopy...A single stool sample was collected from each child. Duplicate Kato–Katz slides were prepared from each sample and examined on the same day to determine S. mansoni infections." Touré et al. 2008, Pgs 780-781.

- 21

"Of 1727 schoolchildren recruited at baseline, 763 were successfully traced and re-examined at both follow-ups with three complete sets of longitudinal parasitological data on S. haematobium...Baseline characteristics of children successfully followed-up showed that they had a lower mean age (9.6 years versus 11.0 years; P0.01), a lower proportion of boys (54.1% versus 59.1%; P0.05), higher S. haematobium prevalence (59.9% versus 53.1%; P0.01) but a similar intensity of S. haematobium infection (93.3 e/10 ml versus 91.2 e/10 ml; P0.05), compared with those who had dropped out. Among 763 children, 322 had valid data entry for S. mansoni at all three surveys. These longitudinal data, together with cross-sectional analysis of three sets of data from the 7-year-old children and two sets of data from the 7–14-year-olds, are presented in this paper." Touré et al. 2008, Pgs 781-782.

- 22

Touré et al. 2008, Pg 782, Table 1.

- 23

Touré et al. 2008, Pg 782, Table 1. Note to table: "All data at 1 or 2 years post-treatment were significantly lower than at baseline (all P 0.01)."

- 24

Data from Touré et al. 2008, Pg A, Table 4. Note to table: "All data at 2 years post-treatment were significantly lower than at baseline (all P 0.05). No significant difference was found between 1 year post-treatment and baseline or between 2 years and 1 year post-treatment (P > 0.05)."

Chart from Touré et al. 2008, Pg 783.

- 25

"In addition to the cohort follow-up, a cross-sectional survey was conducted during the second follow-up (2 years post-treatment), in which a group of children (7–14 years old) outside the original cohort were randomly selected and examined in the sentinel schools. The number, age and sex structures were matched to those in the cohort who were present at the second follow-up in each school." Touré et al. 2008, Pg 781.

- 26

Touré et al. 2008, Pg 784, Table 2.

- 27

Chart from Touré et al. 2008, Pg 783.

- 28

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Burkina Faso: Impact."

- 29

SCI's website does not provide a source for this data. We also searched Google Scholar for "Schistosomiasis AND Burkina Faso," and we consulted the references section of Fenwick et al. 2009, a summary of SCI's work up to 2008.

- 30

"We now report the impact of biennial treatment strategy on urinary schistosomiasis through both school- and community-based drug deliveries for school-age children in Burkina Faso in western Africa...Sentinel schools were randomly selected from all schools in four priority regions targeted in 2004. Within each school, 180 children were selected randomly from each of the 7-, 8- and 11-year- old groups with approximately equal numbers of boys and girls in each age group. However, due to number and gender restrictions in each age group in each school, the actual age range was expanded to 6–14 years. Where the total number was not met in one school, the closest school with the same ecological conditions was selected. As a result, a cohort of 1727 schoolchildren was randomly selected at baseline from 16 schools. The cohort children were examined at baseline and followed up 1 year post-treatment (in 2005) and 2 years post-treatment (in 2006)." Touré et al. 2008, Pgs 780-781.

- 31

"In Niger, where urinary schistosomiasis is endemic along the Niger River valley and in proximity to ponds, a national control programme for schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminth was launched in 2004 with the financial support of the Gates Foundation through the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative." Tohon et al. 2008, Pg 2.

- 32

"Eight villages located in schistosomiasis endemic regions were randomly selected to represent the two main transmission patterns in Niger: six villages located near permanent (Tabalak, Kokorou) or semi-permanent (Kaou, Mozague, Rouafi, and Sabon Birni) ponds and two (Saga Fondo, Sanguile) located along the Niger River. The villages represented the south-western region (Tillabe ́ry) and the central-northern region (Tahoua) of the country, with four villages from each region...Both male and female schoolchildren aged 7, 8 and 11 years were the study population." Tohon et al. 2008, Pg 2.

- 33

"Three rounds of data collection have been completed: baseline (Oct-Nov 2004); follow-up one year post-treatment (Oct-Dec 2005 and March-April 2006); and follow-up two years post treatment (Nov-Dec 2006 and Jan-May 2007)." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Niger: Impact."

- 34

"A total of 89% of the initial sample group were re-examined one year after baseline data collection and the first round of treatment with praziquantel and albendazole...Compared to those children who remained in the study cohort, the 216 children who dropped out after the initial survey differed significantly in the prevalence of S. haematobium infection (75.4% vs. 78%, respectively), but had less frequently heavy-intensity infections (22.8% vs. 16.5%, respectively). On the other hand, they did not differ in mean age (8.7 vs. 8.9 years, respectively), in the prevalence of anaemia (61.9% vs. 59.7%, respectively) nor in mean haemoglobinemia (11.04 g/dl vs. 11.03 g/dl, respectively)." Tohon et al. 2008, Pg 4.

- 35

Tohon et al. 2008, Pg 5, Table 2.

- 36

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Niger: Impact."

- 37

SCI's website does not provide a source for this data. We searched Google Scholar for "Schistosomiasis AND Niger," and we consulted the references section of Fenwick et al. 2009, a summary of SCI's work up to 2008.

- 38

"Eight villages located in schistosomiasis endemic regions were randomly selected to represent the two main transmission patterns in Niger: six villages located near permanent (Tabalak, Kokorou) or semi-permanent (Kaou, Mozague, Rouafi, and Sabon Birni) ponds and two (Saga Fondo, Sanguile) located along the Niger River. The villages represented the south-western region (Tillabe ́ry) and the central-northern region (Tahoua) of the country, with four villages from each region...Both male and female schoolchildren aged 7, 8 and 11 years were the study population." Tohon et al. 2008, Pg 2.

- 39

"In 2004 national control activities recommenced in the country with support from the SCI." Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 5.

- 40

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Mali: Impact."

- 41

SCI's website does not provide a source for this data. We also searched Google Scholar for "Schistosomiasis AND Mali," and we consulted the references section of Fenwick et al. 2009, a summary of SCI's work up to 2008.

- 42

Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, June 17, 2010.

- 43

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Tanzania: Impact."

- 44

SCI's website does not provide a source for this data. We also searched Google Scholar for "Schistosomiasis Control Initiative AND Tanzania," and we consulted the references section of Fenwick et al. 2009, a summary of SCI's work up to 2008.

- 45

Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 9.

- 46

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Burundi: Impact."

- 47

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Rwanda: Impact."

- 48

- Uganda: "We enrolled 4351 children from 37 schools, of which 2815 (64.7%) were traced and treated at one year follow-up and 1871 (43.0%) at two year follow-up." Kabatereine et al. 2007, Pgs 93-94.

- Burknia Faso: "Of 1727 schoolchildren recruited at baseline, 763 were successfully traced and re-examined at both follow-ups with three complete sets of longitudinal parasitological data on S. haematobium...Among 763 children, 322 had valid data entry for S. mansoni at all three surveys." Touré et al. 2008, Pgs 781-782.

- Niger: "Of the 1656 children recruited at baseline, 1193 (72.04%) were successfully followed-up in both year 1 and year 2 surveys." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Niger: Impact."

- Mali: "Of the 2619 children enrolled at baseline, 1511 (57.69%) were successfully followed-up at both the 1st and 2nd follow-up surveys." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Mali: Impact."

- Tanzania: "Out of the 3145 children enrolled in the initial baseline survey, 2044 (65%) were successfully followed up at one year post treatment." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Tanzania: Impact."

- 49

SCI director Alan Fenwick reports the years and countries for which monitoring and surveillance data was collected in Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 7, Table 2. Details on what data and technical details we've seen are available in the previous section.

Does SCI report having collected data? Uganda Burkina Faso Mali Niger Tanzania Zambia Baseline Yes and we have details Yes and we have details Yes and we have data, no details Yes and we have details Yes and we have data, no details Yes and we have not seen results Year 1 Yes and we have details Yes and we have details Yes and we have data, no details Yes and we have data, no details Yes and we have not seen results Yes and we have not seen results Year 2 Yes and we have details Yes and we have details Yes and we have data, no details Yes and we have data, no details Yes and we have not seen results No Year 3 Yes and we have not seen results Yes and we have data, no details No Yes and we have not seen results No No Year 4 Yes and we have not seen results No No Yes and we have not seen results No No - 50

"In 2006, the SCI was a founding partner of the Global Network for Neglected Tropical Disease Control (GNNTDC) and expanded its remit to integrating the control or elimination of seven NTDs." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "About Us."

- 51

Alan Fenwick, email to GiveWell, February 1, 2011.

- 52

"Our monitoring and evaluation activities include checking that drugs have been delivered by going into schools and asking the children whether they've been treated, and asking the teachers whether they've been well trained. We also test the efficacy of the drug by doing stool and urine tests." Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, June 17, 2010.

- 53

Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, February 16, 2011.

- 54

- Uganda: "The first country to implement a control programme on a national scale...Uganda implemented the SCI-supported control programme in April 2003." Kabatereine 2007, Pg 91.

- Burkina Faso: "Some small-scale control activities with treatment had taken place in some areas in the past,11,13 but the na- tional control programme did not start until 2004." Touré et al. 2008, Pg 780.

- Niger: "Niger’s National Schisto- somiasis and Soil-Transmitted Control Programme (PNLBG) was launched at 2004." Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 5.

- Mali: "In the following years many planned activities were not implemented due to limited financial resources but finally in 2004 national control activities recommenced in the country with support from the SCI." Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 5.

- Tanzania: "The failure to embrace a national treatment programme has been due primarily to the costs involved in reaching the millions of individuals estimated to be at risk of infection, and the Ministry of Health was never able to support treatment within their budget. In October 2003, the Tanzanian National Plan was approved for funding by the SCI as a step towards developing a sustainable control programme." Kabatereine et al. 2006, Pg 334.

- Zambia: "The ‘ Zambian Bilharzia Control Programme ’ (ZBCP) was established in 2004 to develop a MoH and MoE joint strategy for bilharzia and worm control. The MoE was already in receipt of a grant from the United States Agency for Inter- national Development (USAID) for implementing training and treatment in some schools on a small scale in two provinces, Eastern and Southern, which was known as the ‘School Health and Nutrition programme ’ (SHN)." Fenwick et al. 2009, Pg 4.

- 55

"Due to the lack of funds, there has been no national control programme on these NTDs, and therefore, there are very large numbers of people who have never been treated." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Neglected Tropical Diseases in Mozambique," Pg 4.

- 56

"Drug distribution channels:

- School-based delivery for school children. School teachers will be trained to carry out drug distribution at schools.

- Community-based delivery for school-aged children who are not attending school and for community adults at high risk. Community Drug Distributors (CDD) will be trained to deliver the drugs at community.

- Health centre-based delivery. Drugs will be made available at health centres for those in the community who do not qualify for MDA and who request for treatment. Health workers at the centres will be trained.

Drug distributors need a minimum of one day’s training to understand the basis for calculating dosages, the necessary actions to deal with side-effects and treatment record keeping and reporting." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Neglected Tropical Diseases in Mozambique," Pg 23.

"For schistosomiasis and STHs, treatment will be conducted through schools by the teachers. For LF, treatment will be conducted through community directed treatment, by the CDDs and community health agents, managed by the district medical officer." Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "Proposal by SCI, Imperial College to Manage the Program for Integrated Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Côte d'Ivoire," Pg 23. - 57

See our overview of priority programs.

- 58

For more details see our summaries:

- 59

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, "What We Do."

- 60

GiveWell: You indicated to us that if you received additional donations, you would spend these funds on research, smaller programs, extra travel, and microscopes. Can you tell us how much can be productively used on each of these specific expenses? What research would you do? Where you would support smaller programs?

SCI: "It all depends on the donations – currently we are getting small donations amounting to approximately $100,000 per year – We use this money 100% for treatment – we buy drugs, ship them to small project leaders in Cote D’Ivoire and Mozambique – no overheads, no staff time all into the field.

We would do the same for up to double this amount. If our donations exceeded this then we would start a larger scale campaign in a selected country and would need staff time and travel to oversee the larger piece of work."

Alan Fenwick, email to GiveWell, February 1, 2011. - 61

Alan Fenwick, phone conversation with GiveWell, June 17, 2010.