We discontinued the "standout charity" designation

Living Goods was designated a GiveWell standout charity, but we stopped publishing a list of standout charities in October 2021. More information is available in this blog post.

Standout charities were organizations that did not meet all of our criteria to be GiveWell top charities, but stood out from the vast majority of organizations we considered. However, we prioritized directing funding to our top charities. More information about standout charities is linked here.

We are no longer maintaining the review of Living Goods below.

Published: November 2014

Since publishing this review, we have a mid-2016 update on Living Goods and notes from our conversations with Living Goods in May 2017, June 2018, June 2019, February 2020, and August 2020. In September 2016, the authors of the randomized-controlled trial of Living Goods' program posted a discussion paper on the study (archived version). We had a conversation with one of the authors of that trial in August 2019.

October 2021 update: We are aware of an ongoing randomized controlled trial that will measure the effect of Living Goods’ program at a larger scale than the original trial, which is referenced on the page below.1 We plan to revisit this program once the results of the larger-scale trial are available.

Summary

What do they do? Living Goods runs a network of Community Health Promoters (CHPs) who sell health and household goods door-to-door in their communities in Uganda and Kenya and provide basic health counseling. Living Goods also provides consulting and funding to BRAC to run a similar network in Uganda and to other organizations to run similar networks in other locations.

Does it work? The main evidence for Living Goods’ impact is a randomized controlled trial that found that the program caused a 27% reduction in under-5 mortality. The full details of this study are not yet publicly available. We have some questions about this study that we cannot yet discuss because the authors are in the process of submitting the final report for publication. We plan to publish a review of the study once the authors have published the full report. Living Goods collects ongoing monitoring data on various aspects of its programs; we have limited confidence in the quality of this data, which raises questions about our ability to learn about the impact of future work. We do not know how effective Living Goods’ work with its partners has been.

What do you get for your dollar? We estimate that Living Goods' cost per life saved will be roughly $10,000 in 2014-2016. Making assumptions that we would guess are particularly optimistic about Living Goods, we estimate the cost per life saved at about $4,400. Pessimistic assumptions lead to an estimate of about $37,000 per life saved.

Is there room for more funding? Living Goods is seeking about $10 million per year for the next 4 years to scale up its program in Uganda fivefold, up from $3.3 million raised in 2013. It is currently in discussions with a number of its core funders who have expressed interest in backing the scale up. No funds have been committed at this stage. If all proposals to core funders are successful, Living Goods will have a gap of approximately $2 to 3 million per year. Living Goods is also seeking additional funding to co-fund partners to start networks in other countries.

Living Goods is a standout because of its:

- Randomized-controlled trial, which found that Living Goods' program reduced child mortality by a very large amount.

- Standout transparency - it has shared significant, detailed information about its programs with us.

Major unresolved issues include:

- The main evidence for Living Goods' program is a single RCT, whereas other programs we recommend are generally supported by multiple sources of evidence. We have a number of potential concerns about Living Goods' RCT.

- As a result of our limited confidence in how the Living Goods and BRAC programs are monitored, we do not know how much we will be able to learn about the success of the programs in the future.

- The size of Living Goods' funding gap for the next year is highly uncertain because major funders are considering supporting the program. If Living Goods raises enough funds to scale up the program studied with the RCT, it may allocate additional funds to programs with less of a track record.

Table of Contents

- We discontinued the "standout charity" designation

- Summary

- Our review process

- What do they do?

-

Does it work?

- Do the products that CHPs sell improve health and save lives?

- Does Living Goods increase access to care and quality of care?

- What does the randomized controlled trial of Living Goods’ program say about its impact?

- What does Living Goods’ ongoing monitoring say about its impact?

- Has Living Goods’ work with partners had an impact on those projects and have those projects improved or saved lives?

- Do the products that CHPs sell provide economic benefits?

- Possible negative or offsetting impact

- What do you get for your dollar?

- Is there room for more funding?

- Living Goods as an organization

- Sources

Our review process

We first considered Living Goods in 2009 and noted that it stood out for subjecting its program to a rigorous evaluation. In 2012, we spoke with Living Goods to get an update on its work and its randomized controlled trial (RCT; conversation notes). Living Goods told us at that time that the results from the RCT were not going to be reliable due to spillover of the intervention into control locations and incorrect matching of the treatment area and the treatment survey area – issues that reduce the statistical power of the study.2

In 2014, Living Goods informed us that the results of the RCT were available and that the effect on mortality was large enough to overcome the problems with statistical power. This year, in order to publish an interim review of Living Goods, we spoke with Living Goods twice (notes from May 2014 here and forthcoming for July 2014) and reviewed documents that it sent us in response to our questions about the RCT, financial statements and budgets, product offerings and sales records, metrics reports, accuracy checks on CHP reports, CHP selection process, CHP dropout rates and profitability, and program performance.

Since finalizing our interim review and determining that Living Goods was a contender for a recommendation, we met with Living Goods in October 2014, requested additional documents, conducted a site visit to Living Goods' program in Uganda in October 2014 (see notes and photos), and spoke once more with Living Goods in November 2014. We incorporated what we learned from discussions, documents, and the site visit into this review.

Previous versions of this page:

What do they do?

Living Goods has two main activities:

- Running a network of agents who sell health and other products door-to-door in Uganda and Kenya and who provide some basic health services.

- Consulting with other organizations on issues related to running similar agent-based systems in Uganda and other locations and funding some of these projects.

We discuss each of these more below.

Running a network of Community Health Promoters

Living Goods describes its network of agents as follows:3

Recruiting and training

Living Goods recruits new CHPs through referrals from existing CHPs, community groups, other NGOs, and religious and local leaders.4

Criteria for new CHPs include: ability to spend two hours per day on CHP activities, 25-45 years old with 7 or more years of schooling, active in her community, fluent in local language and able to read and communicate in basic English.5

Candidates are asked to complete an interview to test their communication skills and engagement,6

attend a two week training course in health and business, and pass a test at the end of the course.

Training covers diagnosis, treatment, and recognizing danger signs that require referral to health facilities, as well as business and sales skills.7 After a CHP passes training, she spends her first two weeks conducting a census of all of the households in her designated area and collecting phone numbers and other key information.8 During this census, CHPs note which households have children under-5 and pregnant women.9

Those who pass the test are required to invest about $30 in initial supplies; Living Goods offers 6-month loans to cover part of the investment.10 Living Goods provides CHPs with a “business-in-a-bag,” which includes uniforms and promotional materials, and a phone.11 Living Goods also provides ongoing in-service training for CHPs.12

Living Goods told us that it interviews about five applicants for every applicant that advances to the training course and that about 5-10% of trainees do not pass the test at the end of the training course.13

Products

In Uganda, CHPs sell preventative health goods (fortified foods, mosquito nets, malaria prophylaxis, vitamins and minerals), treatments (malaria treatments, ORS and zinc, antibiotics, deworming pills, medicines for pain, coughing, and colds), reproductive health goods (delivery kits, menstrual pads, contraceptives), hygiene goods (soap, diapers, toothpaste, toilet paper), and household goods that Living Goods has selected because, in Living Goods’ words, they “have a proven economic benefit and may contribute to improved health” (cookstoves, solar lighting and power, water treatment), among other products.14

CHPs are expected to have medicines for diarrhea (ORS), pneumonia (amoxicillin), and malaria (ACTs) in stock at all times.15

The sales data Living Goods has shared with us is sales to CHPs, from Living Goods branches, rather than sales by CHPs to clients.16 Living Goods notes that both types of products offered and margins can change quickly17 – margins given are from July 2014 and may not reflect long-term trends. It is our understanding that "CHP margins" in the table below are those set by Living Goods; we don't know if they are followed in practice. Living Goods told us that it strongly discourages CHPs from selling at prices other than those set by Living Goods and that CHPs typically follow the price guidelines.18

Sales by product in Uganda between January 2011 and August 2014 (quantities/size per unit vary)19

| Product type | Sales (USD) | % of total sales | Units sold | Living Goods margins | CHP margins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soap | $229,379 | 24.9% | 324,381 | 1-13% | 4-24% |

| Cookstoves | $204,434 | 22.2% | 51,843 | 0-25% | 11-31% |

| Fortified food | $89,109 | 9.7% | 243,718 | 4-19% | 6-11% |

| Malaria treatments | $65,760 | 7.1% | 93,284 | 23% | 33% |

| Solar lighting and power | $62,455 | 6.8% | 3,041 | -40-30% | 2-46% |

| Delivery kits | $57,137 | 6.2% | 18,115 | 20% | 10% |

| Diapers | $36,027 | 3.9% | 16,771 | 10% | 9% |

| Pain, cough & cold | $34,579 | 3.8% | 35,442 | 9-37% | 8-66% |

| Menstrual pads | $27,826 | 3.0% | 20,652 | 7-17% | 8-12% |

| Contraception | $25,673 | 2.8% | 42,327 | 20-33% | 28-44% |

| ORS and zinc | $13,829 | 1.5% | 74,419 | 10-26% | 7-33% |

| Deworming | $10,874 | 1.2% | 6,588 | 36% | 48% |

| Mosquito nets | $8,397 | 0.9% | 2,579 | 12-24% | 7-23% |

| Antibiotics | $8,190 | 0.9% | 6,990 | 25% | 44% |

| Other (e.g. vitamins and minerals, fuel, water treatment, toothpaste) | $47,817 | 5.2% | 97,303 | 0-75% | 5-100% |

| Total | $921,486 | 100.0% | 1,037,453 |

Living Goods’ program in Kenya is newer,20 smaller, and offers fewer products. CHPs in Kenya do not currently offer treatments, which are key to Living Goods’ goal of reducing child mortality. They do offer mosquito nets, fortified foods, contraceptives, and delivery kits, though these account for a small portion of sales to date. Living Goods told us that its current focus in Kenya is on selling “durables that deliver proven economic impact” such as high-efficiency cookstoves and solar lights.21

Sales by product in Kenya between July 2013 and July 201422

| Product type | Sales (USD) | % of total sales | Units solds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cookstoves | $29,780 | 56.5% | 2,155 |

| Solar lighting and power | $11,064 | 21.0% | 476 |

| Water filters | $3,196 | 6.1% | 598 |

| Menstrual pads | $1,578 | 3.0% | 1,095 |

| Business materials | $1,494 | 2.8% | 963 |

| Diapers | $1,447 | 2.7% | 386 |

| Fortified food | $1,349 | 2.6% | 15,384 |

| Other (e.g. fuel, contraception, delivery kits, mosquito nets) | $2,807 | 5.3% | 3,786 |

| Total | $52,715 | 100.0% | 24,843 |

Health services

In addition to going door-to-door selling products, CHPs are asked to:

- Provide households with advice on topics including nutrition, family planning, hygiene, and use of preventative tools such as bed nets, water treatment, clean stoves, and solar lights.23

- Evaluate the health of children in the household and diagnose illnesses, using the Integrated Community Case Management (ICCM) system.24

- Conduct follow-ups with children they have treated and, if necessary, refer the children to other healthcare providers.25

- Give their phone number to clients and respond to calls when asked to provide treatment.26

- Track pregnancies and make 2-3 visits during pregnancy to provide education and vitamins, check for risk factors, sell delivery kits, and encourage women to use health facilities for antenatal and delivery care. CHPs receive small financial incentives for registering pregnancies and making pre- and post-natal visits.27

- Visit mothers shortly after they give birth and once more in the first week to “ensure proper newborn care practices.”28

- Hold community events to provide health education, at least twice per month.29

Oversight

CHPs are overseen by Branch Managers. Branch Managers are expected to visit or talk to each CHP at least once per month30

and collect data from CHPs on pregnancy registrations, treatments provided to children under 5, and other activities.31

Living Goods told us that during their field visits with CHPs, Branch Managers are expected to evaluate CHPs on several criteria:32

- Appearance: for example, checking that CHPs have a sign on their home indicating that they work for Living Goods and that they are wearing their uniform.

- Inventory: checking that CHPs have a sufficient amount of key treatments.

- Health knowledge: evaluating CHPs’ competency in diagnosing key illnesses and providing antenatal and postnatal care.

- Product knowledge: evaluating CHPs’ knowledge of key benefits of products.

- Selling skills.

We do not have a strong sense of the quality of Branch Managers’ evaluations of CHPs, and we have not seen documentation to support that Branch Managers carry out these evaluations once per month with all CHPs as planned.

Based on these reports and sales records, Branch Managers are asked to rank CHPs, occasionally give bonuses to top performers, provide coaching to medium and low performers, and dismiss the lowest performers.33 Criteria for high performance includes over $63 of product purchases, 7 or more registered pregnancies, 13 or more malaria treatments and 6 or more diarrhea treatments per month.34

Field Supervisors are responsible for supervising Branch Staff and monitoring the performance of Living Goods branches. They are expected to be in touch with branch management daily and visit branches frequently to answer questions, listen to challenges, and help find solutions to problems. Living Goods looks for Field Supervisors that have backgrounds in sales, health education, and community outreach.35

Planned smartphone system

In the future, Living Goods plans to require all of its CHPs to use Android-based smartphones during visits with customers.36

This system will:

- Allow CHPs to keep electronic records of their customers and their past activities.37

- Assist CHPs with accurate diagnosis and treatment by prompting them with questions for the patient and then providing a diagnosis and treatment recommendation based on the answers.38

- Enable branches to collect data on CHPs’ sales and treatment activities in real time and linked to GPS coordinates.39

Living Goods has begun using its smartphone system in four of its eight branches, training 100% of the agents from three of them on the Android platform in October 2014 (as of this writing), with plans to move the rest to the system in the coming months.40

Living Goods told us that it expects this new smartphone system to reduce its costs of data collection and provide better monitoring and customer data, as well as make it easier for Living Goods to follow up and spot check agent-registered treatments and pregnancies.41

Partnerships

Living Goods has worked intensively with BRAC in Uganda and provided consulting services to PSI, The Clinton Foundation, and Marie Stopes International.42

BRAC partnership

Living Goods began, in 2008, as a partnership with BRAC to operate a network of CHPs in Uganda, and in 2009 launched a directly-managed network of CHPs using the same model.43

Living Goods has provided both technical and financial support, totaling over $2 million, to BRAC for the CHP program.44

BRAC has 128 branches with active CHPs in Uganda, but only 24 of these branches currently receive significant funding from Living Goods and have additional features, such as incentive payments for CHPs and a higher number of CHPs per branch.45

BRAC- and Living Goods-managed programs generally operate under the same model, but there are several differences between the programs, including:

- BRAC usually works in poorer, more rural areas.46

- BRAC sells a slightly different mix of drugs and products. For example, BRAC does not sell antibiotics to treat pneumonia because it does not yet have permission to sell antibiotics in Uganda.47

- BRAC and Living Goods have slightly different CHP recruitment, training, and certification processes.48

- BRAC provides a somewhat broader range of health services. For example, its CHPs also focus on immunizations and family planning.49

- Living Goods has a more selective process for hiring branch staff and compensates its branch staff more highly.50

- BRAC and Living Goods have slightly different incentive payments for CHPs.51

- BRAC has invested more staff time in antenatal care.52

- During the RCT, BRAC’s cost per CHP was roughly 50% lower because:53

- BRAC operates at a larger scale, so its management costs per CHP were lower.

- BRAC did not provide incentive payments to CHPs for some of the RCT period.

- Other differences in BRAC’s CHP program (listed above) generally reduced its costs relative to Living Goods’ program.

The RCT discussed below includes both BRAC and Living Goods branches.

Other partnerships

As of 2014, Living Goods is actively working with one additional organization: PSI. It previously worked with PSI in Mozambique and is now working with PSI in Myanmar. In 2014, Living Goods began working with PSI Myanmar to provide “high-touch technical assistance to PSI to design and implement a replication of our Uganda model beginning in two townships.” PSI Myanmar will pay Living Goods over three years for its work, which Living Goods expects to cover most of its costs for the project.54

Living Goods has also provided technical assistance to Marie Stopes International, which was working to create a community health worker network in Kenya,55 and to the Clinton Foundation, to help design a pilot in Peru for an entrepreneurship program.56

Living Goods has three full-time staff members who focus on partnerships. A couple additional staff allocate a percentage of their time to this as well.57

Spending breakdown

We have seen expenditure data for Living Goods for 2012 and 2013 and a budget for 2014.58 Both of the tables below exclude the cost of goods. In both 2012 and 2013, Living Goods fully recovered the cost of goods (and made a margin – see third table below), and it expects to in 2014 as well. When the cost of goods are included in the total for 2012 and 2013, it accounts for about 7% of expenditures in those years.

Expenditures by type (in millions)

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | % of expenditures 2012-2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US-based expenses | $1.17 | $1.71 | $1.27 | 41% |

| Country-level expenses | $0.31 | $1.06 | $2.07 | 34% |

| Branch Offices and Transport | $0.11 | $0.20 | $0.23 | 5% |

| Marketing and Promotion | $0.12 | $0.11 | $0.13 | 4% |

| Training | $0.05 | $0.04 | $0.03 | 1% |

| Sub-Grant to BRAC | $0.60 | $0.15 | $0.36 | 11% |

| Capital Expenditures | $0.08 | $0.20 | $0.14 | 4% |

| Total | $2.43 | $3.47 | $4.22 |

Expenditures by program (in millions)

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | % of expenditures 2012-2014 | excluding unallocated | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LG Uganda | $0.59 | $0.79 | $1.26 | 26% | 44% |

| LG Kenya | - | $0.50 | $0.79 | 13% | 22% |

| BRAC Uganda | $0.60 | $0.15 | $0.36 | 11% | 18% |

| Other partnerships | $0.09 | $0.32 | $0.53 | 9% | 16% |

| Unallocated (primarily US-based operations) | $1.16 | $1.71 | $1.28 | 41% | N/A |

| TOTAL | $2.43 | $3.47 | $4.22 |

Margin on goods sold

| 2012 | 2013 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of goods | $172,726 | $285,808 | $458,534 |

| Wholesale sales revenue | $261,586 | $393,663 | $655,249 |

| Damages, expired, and write downs | $13,394 | $39,966 | $53,360 |

| Final margin | 29% | 17% | 22% |

Living Goods organizational structure

Living Goods’ staff consists of about 5 US-based staff, about 35 staff on country-level teams in Uganda and Kenya, 2 field supervisors, and a Branch Manager and Assistant Branch Manager at each of eight branches in Uganda and one Branch Manager in Kenya.59 Country-level staff include staff specializing in training, product development, sales, health impact, logistics, technology, finance, talent, monitoring, and partnerships.60

Does it work?

To evaluate Living Goods’ impact, we considered:

- Do the health products that CHPs sell improve health and save lives?

- Does Living Goods increase access to care and/or quality of care?

- What does the randomized controlled trial of Living Goods’ program say about its impact?

- What does Living Goods’ ongoing monitoring say about its impact?

- Has Living Goods’ work with partners had an impact on those projects and have those projects improved or saved lives?

- Do the products that CHPs sell provide economic benefits?

In short:

- The main evidence for Living Goods’ impact is a randomized controlled trial that found that the program caused a 27% reduction in under-5 mortality. The full details of this study are not yet publicly available. We have some questions about this study that we cannot yet discuss. We plan to publish a review of the study once the authors have published the full report. (More)

- Living Goods collects ongoing monitoring data on various aspects of its programs. We have not seen reports on many aspects of its monitoring, and we have limited confidence in the quality of the monitoring data that has been shared with us, which raises questions about our ability to learn about the impact of future work. (More)

- We have some information about the impact of Living Goods’ partnership with BRAC (mostly from the randomized controlled trial of its program). We do not know how effective Living Goods’ work with its other partners has been. (More)

Details follow.

Do the products that CHPs sell improve health and save lives?

Living Goods says that it “aim[s] to reduce under-five mortality by focusing on an ICCM+ approach, [which] includes quality diagnosis and treatments for pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, encouraging prevention and healthy behaviors, and improving maternal and newborn health, especially in the perinatal period.”61 We have not completed recent evidence reviews for artemisinin-combination therapy (ACT) for malaria (older review of the program here), antibiotics to treat pneumonia or oral rehydration salts to treat diarrhea, but we believe that there is relatively strong evidence to support these programs. We have not researched the efficacy of interventions for newborn conditions. Living Goods told us that it focuses on newborn conditions in particular because it has found that a large portion of child deaths occur in the first month of life and that there are interventions that can significantly reduce this mortality.62 Living Goods’ RCT supported this; it found that 75% of deaths recorded in the RCT were in the first year and 52% in the first month of life.63

CHPs also sell deworming medications and mosquito nets, on which we have completed evidence reviews and believe to be effective. However, the manner in which these products are distributed (one-off purchases rather than community-wide distributions) may affect their impact. In addition, these products account for a small portion of Living Goods’ sales.

Other products and services may also contribute to health, but we have not reviewed the evidence on their impact. Such effects might include improved maternal health from pregnancy support and post-natal visits, reduced indoor air pollution and injuries resulting from use of cookstoves and solar lighting, improved nutrition from the use of fortified foods and vitamins and minerals, and reduced infections from the use of delivery kits and soap for handwashing.

Note that evidence that the products CHPs supply improve health would not be sufficient to demonstrate Living Goods’ impact, because households might obtain the products from other sources in the absence of CHPs. However, this evidence helps provide context on whether the RCT results are plausible.

Does Living Goods increase access to care and quality of care?

Living Goods notes that the drugs it sells are free in public facilities, but that clients may prefer to buy from CHPs because of the cost of traveling to facilities and possibility that the facility will be out of the medicine. According to Living Goods, clients may also be reluctant to buy drugs from other private providers because of the risk of getting a counterfeit medicine.64 Living Goods sent us a study conducted at the midline of its RCT that claims that both availability of counterfeit drugs and drug prices decreased at private retailers in areas where CHPs worked.65 According to the study, about 37% of private drug shops in the areas it studied sold fake ACT drugs,66 and availabilty of fake ACTs was about 50% lower among non-Living Goods sellers in the areas where Living Goods worked.67 Additional results on these potential effects will be made available when the full RCT is published. We have not yet reviewed the study or vetted other claims about how and why consumers choose to obtain medicine.

Living Goods also told us that it recently developed a five-step quality management process for all of its medicines that will be implemented in 2015.68 We do not yet know the details of this process.

Anecdotal evidence from our site visit

Note that areas that we visited and CHPs and customers we interacted with were not selected randomly (more details in footnote).69

Does Living Goods increase access to care and/or quality of care? Where would clients obtain health products from in the absence of CHPs?

Overall, the evidence from our site visit seemed broadly consistent with the possibility that Living Goods is improving access to healthcare and quality of healthcare in the areas where it works. For example, it may be increasing access to essential medication by having lower prices than competitors and a convenient delivery model, and it may be improving quality of care by building trust with its customers. However, we put little weight on this evidence because it is based on limited and potentially non-representative information.

On our site visit, we learned about some customers’ reasons for using Living Goods’ services. For example:

- Some customers told us that Living Goods’ prices are lower than its competitors’ prices.70

- It seemed that some customers buy products from Living Goods because it is convenient.71

- Some customers seem to use Living Goods’ services because they have strong relationships with their CHPs.72

We also visited some private drug sellers in order to try to understand the other healthcare options that were available to people in areas that we visited. These shops seemed to have key medicines and products in stock, such as pneumonia medications, rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for malaria, and antimalarials. We were not able to determine anything about the quality of these drugs. It generally seemed that private drug sellers were reasonably accessible in the areas we visited.73

Living Goods staff gave us more information about other healthcare options that are available to people near the Living Goods Tula branch. They told us:74

- The area is supposed to have Village Health Team members (government community health workers, called “VHTs”), but in practice they rarely work because they are not paid.

- Government health centers provide free treatment, but they are often stocked out of essential medication such as antimalarials. Since travel to these clinics is expensive, some people have stopped attempting to go to them.

- Pharmacies usually have essential medicine in stock but can be expensive. Also, it is often hard to find pharmacies far away from town centers. The cost of a typical course of Artemisinin Combination Therapy (ACT, antimalarials) would be about 5,000 UGX (~$1.83) at a pharmacy.

- Private clinics are known for overcharging for treatment, but they are often the only option far away from town centers. The cost of a typical course of ACT at a private clinic would be 12,000 UGX (~$4.40).

- The cost of a typical course of ACT at a hospital would be 6,000 UGX (~$2.20).

- It would cost about 6,000 UGX (~$2.20) to travel to the nearest government hospital from the area – a significant amount of money for poor members of this community.

- Living Goods sells a treatment course of ACT for 3,000 UGX (~$1.10).

We have not independently vetted this information.

Among the limited sample of people we encountered, it seemed that if Living Goods were not an option they would most likely go to private clinics or pharmacies to purchase treatments.75

Are Living Goods products consistently high quality?

The two Living Goods branches that we visited seemed to be following proper protocols as we understood them. In particular, they seemed to be carefully monitoring the supply, condition, and expiration dates of their medications.76

This generally supports the case that Living Goods offers high quality products, but because our experience on the site visit may have been non-representative and there are many other potential factors that may affect the effectiveness of drug treatments aside from following storage procedures for drugs properly, we consider it to be only weak evidence in support of the quality of Living Goods’ drug treatments.

What does the randomized controlled trial of Living Goods’ program say about its impact?

Researchers conducted a cluster-randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the CHP program in Uganda between 2011 and 2013. The study included both villages served by CHPs managed by Living Goods and villages served by CHPs managed by BRAC.77 The researchers have published an abstract on the study,78 and shared a more in-depth report with us. The more in-depth report is not yet cleared for publication because the authors are seeking publication in an academic journal.79 We have some questions based on the in-depth report that we cannot yet discuss. We plan to publish a review of the study once the authors have published the full report.

The study included 214 rural villages and surveyed 8119 households. It found that the program reduced under-five mortality by 27%.80 The under-five mortality effect was smaller (though still statistically significant) in BRAC branches than in Living Goods branches, but the cost per CHP was lower in BRAC branches as well.81 The authors note:82

We find these results highly promising, however we have not fully vetted the results and note that the strongest programs we have considered are backed by multiple studies, while there has only been one rigorous study of the Living Goods program. In addition, from the information we have seen, we have the following concerns:

- It appears that villages may have been carefully selected for inclusion in the sample (i.e. the list that was then divided into treatment and control) and that only a selection of Living Goods and BRAC branches were considered for the list. While this shouldn’t bias the results of the study, it could affect how replicable the results are in other locations.

- With such a program it is not possible to hide from participants whether or not they received the intervention and outcome measures rely on self-reports of events that may have occurred a few years in the past. Those who knew they were part of the program (because they had interacted with a CHP) may have been influenced to give more positive answers. However, this effect is less likely to impact mortality reports than questions on more subjective or less memorable events.

What does Living Goods’ ongoing monitoring say about its impact?

Performance indicators

Living Goods reports on such metrics as number of malaria and diarrhea treatments provided, % of malaria and diarrhea cases followed up within 2 days, number of pregnancy registrations, % of pregnant women delivering in a facility or with trained help, % of women visited in the first 48 hours after giving birth, and % of referral cases followed up. It reports these metrics for both its directly-managed network and for the BRAC network. We have seen data for January 2012 through June 2014.83

We put limited weight on these metrics because:

- The data for these metrics are self-reported by CHPs, who are evaluated on their performance on such metrics and provided financial incentives for certain behaviors,84 which may incentivize them to inflate their reports.

- There is some evidence that CHPs are inflating the data. Living Goods told us that two main ways it checks the accuracy of these reports are to (a) compare the number of malaria and diarrhea treatments it sells to CHPs, to the number of malaria and diarrhea cases that CHPs report treating,85 and (b) conduct monthly analyses (called “outlier reports”) to identify CHPs who report unusually high numbers of malaria or diarrhea treatments, active pregnancies, and/or pregnancies registered.86 In January to August 2014, CHPs reported about 4% more malaria treatments than Living Goods sold to CHPs and about 32% more diarrhea treatments than Living Goods sold.87 Living Goods notes that because dosages vary by the age of the patient and CHPs may choose to stock up on key treatments, over a short time frame, these figures may not fully match.88 For example, with malaria treatments, the package sold equates to 1 adult dosage, 2 doses for an older child, or 4 doses for a younger child.89 This makes it difficult to correlate sales to actual treatments without knowing the exact age of every treatment (which Living Goods expects to be more feasible with the new Android system).90 Living Goods also shared an example of an “outlier report” with us.91 Living Goods told us that the example report includes data from all CHPs who sell health treatments.92 Of this portion of CHPs, it seems that roughly 20% were determined to have reported an unusually high amount of activity for at least one of the outcomes (malaria treatments, diarrhea treatments, active pregnancies, or pregnancies registered).93

- It appears that Living Goods calculates the % of cases followed up as the total number of follow up visits reported divided by the total number of treatments provided. As a result, this rate can exceed 100%. The rate of cases of malaria and diarrhea followed up was over 100% in every month from February to June 2014, reaching a maximum of 133% in April.94

Randomized follow-ups

Living Goods has stated that it “uses randomized follow-ups to improve quality control and monitoring of treatments."95

Living Goods told us that it conducts or has conducted a few types of randomized follow-ups:

- Sometimes, on their field visits, Branch Managers randomly choose and visit a few households in a CHP’s customer register to verify the accuracy of a CHP’s reported activities.96

- Branch Managers visit a sample of customers who received goods or services from CHPs who were identified by an “outliers” report (mentioned above).97

- In the past, it conducted some randomized follow-ups in order to verify the accuracy of CHPs’ pregnancy registrations and newborn visits because CHPs receive an incentive payment for such activity.98

We have not seen any results from such follow-ups. Living Goods told us that it may collect records from these follow-ups but that the records are not readily available because they are not reviewed by staff at the U.S. office.99

Field reports

Branch Managers began recording their evaluations of CHPs during field visits in August 2014.100

The content of these evaluations is described in the oversight section above. We have not seen data from these evaluations.

Stakeholder reports

Living Goods publishes annual “stakeholder reports” which report, at a high level, on organization and program progress. A few interesting notes from the 2013 report:

- In BRAC’s network "under five diarrhea and malaria treatments and sales per CHP fell due to procurement challenges in the second half of the year that affected pricing."101

- Living Goods "developed credit products for both consumers and agents, with an impressively high repayment rate of over 99%."102 We do not know how the repayment rate was calculated.

- Living Goods conducted surveys of CHPs in both Uganda and Kenya, and reported a selection of positive results.103 Living Goods sent us additional information about the CHP surveys, but we have not yet reviewed it.104

Future monitoring plans

As of November 2014, Living Goods was working to revise and strengthen its monitoring and evaluation strategy. It expects to finalize its strategy in early 2015 and plans to implement any monitoring changes shortly after the strategy is finalized.105

Living Goods told us that its new strategy:106

- Will continue to monitor performance against key performance indicators including prompt treatments, pregnancies supported, newborn visits, in stock rates, and more.

- Will rely on increased use of Android smartphones by CHPs in order to track CHP performance real-time and verify the accuracy of CHPs’ reported activity.107 Living Goods’ goal is to eliminate use of paper reporting and convert all agents to 100% mobile data collection.108

- Will continue to rely on reports that Living Goods currently compiles about outlier cases, discrepancies between treatments and sales, and CHP sales performance.

- Will require CHPs to be retested on their health knowledge and ability to properly diagnose and treat annually. Living Goods may collect reports on the percentage of CHPs who do not pass this “recertification” test.

- Will add monitoring tools to verify the accuracy of CHPs’ reported activity.109

- May add monitoring tools to check the quality of CHPs’ diagnoses and prescribed treatments. The new Android platform includes a step-by-step diagnostic program, which Living Goods expects to improve accuracy and consistency of diagnosis and treatment.110

- May involve tracking new performance metrics, such as percentage of treatments diagnosed within 48 hours of contracting illness, nutrition indicators, and geographic coverage (using mobile GPS data).

- May involve conducting quasi-experimental research, such as by implementing a pre-treatment and post-treatment household survey. This aspect of the monitoring and evaluation strategy is least certain.

Living Goods expects that BRAC branches will also implement any new monitoring that is implemented at Living Goods branches, though it may be a significant amount of time before BRAC branches implement smartphone monitoring.111

Has Living Goods’ work with partners had an impact on those projects and have those projects improved or saved lives?

As discussed above, the RCT on Living Goods’ program includes an evaluation of the BRAC program that it has provided technical and financial assistance to. We have not seen information on whether Living Goods’ work with other partners has been impactful (about 9% of Living Goods’ total budget from 2012-2014 was spent on non-BRAC partnerships).112

Living Goods’ monitoring of BRAC

Living Goods told us that it conducts some monitoring of BRAC’s programs. For example:113

- Each month, BRAC shares reports on its key performance indicators (i.e., number of malaria and diarrhea treatments provided, number of pregnancy registrations, etc.) with Living Goods. Living Goods reviews the reports and follows up with BRAC about any potential issues.

- In the past, Living Goods staff has carried out randomized checks of BRAC branches.

We have not seen any reports on follow ups with BRAC or randomized checks.

Living Goods told us that it is still in the process of determining how it will monitor BRAC's programs in the future.114

BRAC's programs have independent leadership, so Living Goods may have limited ability to affect BRAC's policies and practices.

BRAC’s monitoring

BRAC told us that it invests a significant amount of staff time in verifying the accuracy of its CHPs’ reported activities and to evaluate the quality of the care that CHPs provide.115

However, we have not seen any reports on details of these evaluations. We summarize the details of the monitoring system BRAC described to us in this footnote.116

BRAC told us that all monitoring reports are collected and summarized at each level of the organization and flow up all the way to the BRAC country office. The BRAC country office summarizes findings from these reports and discusses them at a monthly meeting.117

We learned about BRAC's monitoring shortly before publishing this report. It is our impression from our conversations with Living Goods that it does not regularly request BRAC’s detailed field-level monitoring results.118 We have not yet asked BRAC to share documentation from its monitoring.

Anecdotal evidence from our site visit

During our 2014 site visit to a BRAC branch, we noticed a few potential, likely minor issues:

- CHPs told us that some CHPs sell drugs to drug shop owners, which is against BRAC-LG rules.119

- The branch that we visited seemed to have very few deworming pills (albendazole) left in stock.120

- CHPs reported sometimes running out of medicines and restocking seemed to require paying reasonably expensive travel fees.121

We put limited weight on these concerns because they are based on anecdotal evidence.

BRAC also told us that it is working to strengthen its procurement supply chain because its branches sometimes experience stock-outs.122

Do the products that CHPs sell provide economic benefits?

Some Living Goods products, such as cookstoves and solar energy products, may provide economic benefits to customers by, for example, saving them money on fuel. Living Goods sent us estimates of how much customers who buy cookstoves and solar energy products save.123 Living Goods told us that it estimates that its customers save 50% of their monthly fuel costs on average when using an efficient cookstove, and that typical fuel spending in Uganda tends to be in the range of $20-25 USD per month pre-stove purchase.124 We have not yet reviewed these estimates.

Possible negative or offsetting impact

- Are clients’ problems sometimes misdiagnosed and/or overdiagnosed? We do not know how difficult it is to properly diagnose the various problems that CHPs may come across with a CHP’s level of training. For example, it seems possible that malaria may be difficult to distinguish from pneumonia. Misdiagnosis may cause worse outcomes for clients if they would have sought healthcare providers with better diagnosis skills in the absence of Living Goods’ program. Additionally, since CHPs have a financial incentive to sell more treatments, it seems possible that the Living Goods program could cause CHPs to overdiagnose clients and overprescribe treatments. As discussed in the monitoring section above, Living Goods has told us that it recognizes this concern and has some systems in place to attempt to reduce the likelihood that this occurs, but we are not confident that Living Goods' systems would identify many cases of misdiagnosis or overdiagnosis.

- Are some CHPs harmed by the program? CHPs take on financial risk by joining the program. Living Goods estimates that its CHP turnover rate is about 22% per year, and that 70-80% of CHPs who leave chose to drop out of the program, while the rest are asked to leave.125 We do not know how common it is for CHPs to lose money as a result of their participation.

- Does Living Goods divert skilled labor from other areas? CHPs are fairly well-educated and well-connected members of their communities. Would they have been adding value to their communities in other ways if they were not spending time as a CHP? Given the part-time nature of their work, we would guess that this is not a major concern.

What do you get for your dollar?

Living Goods' estimates

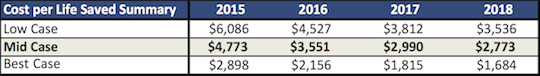

Living Goods has provided estimates of its future cost-per-life saved based on the lives saved per CHP in the RCT and modeling of future costs and numbers of CHPs. These estimates are based on Living Goods Uganda-specific budgets for 2015-2018 and the number of Living Goods-managed agents it expects to have each year. The "mid case" uses the blended mortality reduction estimated by the RCT (25.5%), which includes both Living Goods and BRAC branches, while the "low case" seeks to account for possible reductions in impact during scaling (using 20% for the impact on mortality), and the "best case" uses the mortality reduction observed for Living Goods branches only in 2013 (42%).126

Our adjustments to Living Goods' estimates

Living Goods shared the details of how it calculated its estimates, and we think they are largely reasonable with a few caveats. There are a few additional assumptions we make in our estimates of Living Goods cost effectiveness:127

- Living Goods has included only those costs that it incurs within Uganda or that are allocated to the Uganda program.128 We have included Living Goods' full budget, minus expected program revenue.129 These additional costs support the program directly and indirectly and include US-based costs (e.g., business development, communications and advocacy) and Living Goods’ partnership team. Living Goods told us that it does not include its partnerships team costs in its model of its cost-effectiveness because that team currently has costs but no basis for modeling future associated impact of its spending.130 The partnerships costs represent roughly 17% of Living Goods’ total budget for 2015-2018 and other non-Uganda and non-partnership costs (primarily US-based costs) represent about 10% of Living Goods’ total funding need for those years.131

- The budget Living Goods provided does not include costs of the Kenya program, so these are missing from our model.

- Living Goods' estimates rely on an estimation of the lives saved per CHP based on the 2012 under-5 mortality rate in Uganda. Under-5 mortality fell by about 4-6% per year in Uganda from 2009 to 2012.132 If this trend continues, lives saved per CHP will likely be lower in the future. In some of our scenarios, we have assumed that mortality, in the absence of Living Goods' program, will continue to fall over the next four years.

- In one of our scenarios, we have added an adjustment for contamination of the RCT due to CHPs visiting control group households.133 This contamination could cause the RCT to underestimate the effect of the intervention.

- We have added an adjustment for our subjective guess on whether the RCT results would be replicated if another RCT was done on the scale up program. This adjustment aims to capture both the strength of our belief in the accuracy of the RCT results as well as in the likelihood that Living Goods and BRAC will be able to replicate the results at a greater scale and in somewhat different locations (though still within Uganda). This adjustment is varied across scenarios. However, the average replicability adjustment in our scenarios effectively reduces the mortality reduction in the RCT by about 50%.

- We have varied, across scenarios, the number of years we include in the estimate. Since Living Goods expects its cost per CHP to decline as it scales, it is more conservative to only include costs and benefits for the next 1-3 years than it is to include all 5 years.

Two GiveWell staffers have entered parameters for the various assumptions to derive "pessimistic," "base case," and "optimistic" estimates of Living Goods' cost per life saved (similar in concept to Living Goods' "low case," "mid case," and "best case"). The two staffers used somewhat different assumptions but generated similar estimates:134

- Pessimistic: About $37,000 per life saved

- Base case: About $10,000 per life saved

- Optimistic: About $4,400 per life saved

Details in this spreadsheet.135 In the future, we may ask Living Goods for some additional information that will help us improve the model (details in footnote).136 In the future, we may also conduct further research to help us improve the model (details in footnote).137

Note that the estimate does not take into account any other potential benefits of the program, such as improved health in non-fatal cases or economic benefits from the purchase of money-saving durables such as solar lights, more efficient cook stoves, or water filters (discussed above). The estimate focuses solely on under-5 mortality because this was the primary outcome examined by Living Goods’ RCT. We do not have enough information about Living Goods’ effects on other health outcomes to confidently include them in our analysis.

Average cost per life saved of Living Goods’ Uganda program

The figures discussed above estimate the average cost per life saved by the Living Goods program. This approach is consistent with our approach to estimating cost effectiveness for our top charities and seeks to deal with issues of "leverage" by treating all donor funds the same.

Another approach, and one that Living Goods favors relative to the approach above, would be to attempt to calculate an average cost per life saved for Living Goods’ Uganda program only. This excludes many costs that Living Goods expects to incur regardless of the number of CHPs it supports, namely, U.S. headquarters costs and the costs of supporting the partnership team.

With these assumptions, we estimate a base case of about $7,000 per life saved.138 As noted above, this estimate is not directly comparable with cost effectiveness estimates we have created for other charities.

Is there room for more funding?

Scaling up in Uganda

Scale up plans

Having recently completed the RCT, Living Goods is now aiming to rapidly scale up the networks of CHPs directly managed by Living Goods and managed by BRAC, from about 1,000 CHPs (400 Living Goods, 600 BRAC) to 6,500 CHPs (2,500 Living Goods, 4,000 BRAC).139 Living Goods shared a detailed breakdown of its scale-up plan for networks directly managed by Living Goods with us.140

Living Goods expects its scale-up in Uganda to be similar to its past work in the country.141 Differences may include:

- A greater number of agents per branch.142

- An increased focus on postnatal visits.143

- An increased focus on nutrition products and nutrition education.144

- Work by BRAC on improving the quality of local health facilities, particularly for delivery care, through training, checklists, and new protocols.145

- For the first time, Living Goods will have some male CHPs.146

Living Goods has also noted a couple of ways in which the setting it is working in has changed since the start of the project: bednet coverage is 2-3 times higher and the market price of malaria treatment has been reduced.147 Under-5 mortality in Uganda, according to the World Bank, decreased from 83 per 1,000 live birth in 2009 to 69 in 2012.148

Funding need

In total, Living Goods is seeking funding to support a budget of about $9.6 million per year, including costs incurred by BRAC. Since Living Goods’ overall budget is increasing, it also aims to raise an additional $3 million in reserves (about $2 million in 2015 and about $1 million in 2016).149 It expects to raise some funds from partnership consulting fees and margins on goods sold to CHPs, leaving about $10 million per year that would need to be supported by donor funding.150 In 2012 Living Goods raised $2.8 million, and in 2013 it raised $3.3 million from donors.151 Living Goods told us that it believes there is a decent chance it will reach two-thirds of its funding target for the first year through agreements with funders who have supported its work in the past, but the money has not yet been secured and the funding need will grow each year.152 The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), one of Living Goods’ major core funders historically, will be deciding in Q1 2015 whether to fund Living Goods' scale-up. CIFF has indicated a significant interest in funding up to 50% of Living Goods’ costs for 2015-2018, with the condition that Living Goods raises approximately $1 for every $1 CIFF contributes.153 Regardless of CIFF’s decision, Living Goods is actively seeking funding from new and existing donors to fill its funding gap and plans to use these funds to support scaling up in Uganda and its partnerships and advocacy team’s efforts to help organizations replicate the model in other places.154

Living Goods told us that BRAC is largely relying on Living Goods to secure funding for BRAC's portion of the Uganda scale-up.155

Uganda scale-up budget 2015-2018 (in millions)156

| Expenditures | Program revenue | Donor funding needed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living Goods Uganda | $11.29 | $1.02 | $10.27 |

| BRAC Uganda | $14.98 | $0.93 | $14.05 |

| Partnerships | $6.52 | $3.25 | $3.27 |

| Other (primarily US-based) | $5.68 | - | $5.68 |

| TOTAL | $38.48 | $5.21 | $33.27 |

Operations in Kenya

Living Goods told us that in the past it has used a mix of unrestricted and restricted funding to support its operations in Kenya.157 In 2015, Living Goods told us that it plans to spend about $700,000 in Kenya,158 which is similar to the roughly $750,000 it spent in 2014.159 As far as we know, Living Goods does not have plans to use further unrestricted funds to scale up in Kenya. Living Goods told us that if it decided to significantly expand or change its operations in Kenya, it would find additional independent funding to support this.160

Replication fund

Living Goods has told us that scaling up in Uganda is its top priority, but in order to have the transformational impact it seeks, it wants to demonstrate that the model can work in other markets. To this end, Living Goods and CIFF are discussing creating a fund for replications of its program by partners. If it received sufficient funding for its scale-up, it may allocate unrestricted funds to the replication fund.161 Living Goods has proposed creating a fund of $10-15 million to provide co-funding for programs in three countries that would reach 3-5 million people per country; it estimates that the full cost of a new country program would be $10-15 million,162 so its support would cover 33% of the total. It expects that having such a fund would improve its ability to negotiate and launch new projects with partners.163

It plans to target countries based on:164

- Need/impact: high child mortality rates driven by malaria, diarrhea, respiratory infections, and neonatal conditions; high rates of counterfeit drugs; high drug prices; low rates of use of water filters, clean cookstoves, and solar lights.

- Economics/sustainability: reasonable household purchasing power, and large (over 15 million) populations with high population density.

- Governance: low security risk and a government that will allow the program to sell medicines.

- Current partner presence: Living Goods would prefer to work with partners that already have relationships in country.

Based on these criteria, Living Goods is most strongly considering partnerships in Nigeria, India, Ghana, Zambia, Tanzania, Kenya, and Myanmar.165 Possible partners include PSI, Management Sciences for Health, Marie Stopes International, CARE, BRAC, Save the Children, and Plan International.166

Living Goods as an organization

We have limited observations on which to base an assessment of Living Goods as an organization. However, our sense is that Living Goods is a strong organization:

- Track record: Living Goods is a relatively young organization; it was founded in 2007. Its RCT, though not yet fully vetted, appears to have found strong effects of its program. However, we feel that we have limited information on its track record because we have not seen detailed, high-quality monitoring of its program. We expect to learn more about Living Goods as an organization as we see how it handles the challenges of scaling up its program and tracking the quality of its program as it scales.

- Self-evaluation: Living Goods has invested unusually heavily in understanding the impact of its program by completing a RCT of its program. It has also demonstrated a commitment to collecting information on its program on an ongoing basis, though we believe that this information is less rigorous than that of some of our other top charities to date.

- Communication: Living Goods has communicated clearly and directly with us and given thoughtful answers to our critical questions.

- Transparency: Living Goods has consistently been strong in its commitment to transparency. We have not seen it hesitate to share information publicly (unless it had what we felt was a good reason).

More on how we think about evaluating organizations at our 2012 blog post.

Sources

- 1

- “Status: Ongoing. Start Date: 2016-01-25. End Date: 2021-12-31.” AEA RCT Registry, "Evaluation of Living Goods/BRAC entrepreneurial CHW model in Uganda - Phase II," 2020, section on "Additional Trial Information."

- “A first evaluation of the impact of the CHP program began in 2010 (Björkman Nyqvist et al, 2019). The evaluation was based on a cluster-randomized controlled trial that involved 214 villages in 10 districts across Uganda. . . . The evaluation was based on an endline survey collected at the end of 2013, which covered 7,018 households and 11,563 children under-5 that lived in the same village throughout the trial. . . .

“Following the first study, the program has been massively scaled up across Uganda. The study presented in this submission takes advantage of the scaling up of the program to investigate the following two key questions: 1) Can the reduction in child mortality observed in the “proof-of-concept” study be sustained when the program is scaled-up? 2) What is the impact of scaling up an incentivized community health worker program on existing health service providers?

“This new study involves the same main actors of the first one: program implementers, data collection agency , and funding agency. . . . There are, however, also few important differences: the new study will measure treatment effects over a longer time period, it relies on a much larger sample (500 villages and more than 12,500 households), it exploits a much richer set of data, including survey data from other providers in the community, and it relies on a panel of households identified at baseline, rather than on a cross-section.” AEA RCT Registry, "Evaluation of Living Goods/BRAC entrepreneurial CHW model in Uganda - Phase II," 2020, abstract.

- 2

“LG noted in a document it sent that there have been some issue with the RCT it is currently conducting. We asked about this, and LG told us that there were both changes in the geographic footprint of the model and some flaws in the RCT survey strategy which are rendering the results not reliable from an evaluative point of view.

1. Spillover: Control sites were found to have experienced about 1/3 as much of the exposure to LG as treatment sites.

2. Service area for each agent: They had to guess service areas for each agent when they started and their guesses were quite different from how the program evolved. The RCT was designed with service areas that were much larger in terms of number of households and geographic area than agents are actually able to cover. For example: a significant number of survey-defined areas included 200-400 households, and subsequent research shows that the number of households in a given agent's area is closer to 100. Researchers are concerned that any attempts to ameliorate this effect would compromise randomization.

3. Treatment population not matched to treatment area: LG did a GPS tracking exercise on how far and where agents worked and compared this data to data from the RCT. They found that 80% of the homes actually served by agents were within 500 meters of agents' homes. However, 50% of households in surveyed in the RCT were over 1.2 km from agents homes.

4. There is also some agent activity that is in neither in control or treatment sites, constituting

impacts that will not be detected.”GiveWell's non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Chuck Slaughter, July 20, 2012.

- 3

- Email from Chuck Slaughter, Founder and President, Brad Presner, Director of Analytics, and Lisa McCandless, Director of Development, Living Goods, October 6, 2014

- Email from Chuck Slaughter, Founder and President, Brad Presner, Director of Analytics, and Lisa McCandless, Director of Development, Living Goods, November 24, 2014

- 4

“Recruitment activities include:

1. Mapping out areas where gaps exist or where we should expand CHP

coverage.

2. Meeting with LCs, women’s groups, other NGOs, religious and local leaders to get referrals for CHP candidates.

3. Explaining and distributing CHP candidate referral forms to existing CHPs.

4. Assist Field Supervisors and Training Team with oral interviews,administering exams, and explaining requirements to CHP candidates.”

Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 8. - 5

“Criteria Over the years, Living Goods has found successful CHPs share a few key traits. As you run recruitment activities with local leaders, here are the characteristics you will look for in CHP candidates:

1. Ability to dedicate 2 hours per day to sales and education activities for Living Goods. Keep in mind women with very young children might not be able to dedicate enough time.

2. Minimum 7 years of schooling.

3. 25-45 years old.

4. Fluent in local language(s).

5. Able to read/communicate in basic English.

6. Married (or no other plans to move soon).

7. Friendly, active, and known in her community with connections in social or women’s groups.

8. Previous work experience or training in health or business skills is desired (but not mandatory).

9. Ability to pass a basic math/reading test in English."

Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 8. - 6

“There are no right answers to these questions. The most important aspects of the interview arise from the interaction. Does this person communicate well? Does she understand the questions and respond appropriately? Has she demonstrated genuine interest in the work and the competence to carry it out?” Living Goods CHP Interview Guide.

- 7

- “Every Living Goods agent receives 2-3 weeks of initial health and business training. Agents are trained on all key health topics, including diagnosing, treating and recognizing danger signs for referral. Agents are also trained on important aspects of running a business such as managing working capital, calculating profit, and record-keeping. Finally, agents are trained in best practice sales skills, counseling, and communication.” Living Goods Training & Coaching.

- “To operate as a Living Goods CHP, applicants must:

- Attend two weeks of training and pass the test at the end

- On passing the test, invest UGX 82,000 in the tools and initial inventory to build their business. A 6-month loan is available, with a UGX 25,000 deposit required up-front to get commodities worth 54,000 UGX and a phone worth 270,000 UGX.

- Commit to spending at least 2 hours per day visiting households in their zone.”

- In the future, all CHPs will also be trained to use Android during initial training. ”The full LG training course lasts 12 full work days and covers health (5 days), how to use Android (4 days), and business/sales (3 days).” Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014

- We attended a training for CHPs and new Branch Managers on our 2014 site visit. The teaching methods seemed to be high quality and trainees seemed to be engaged. “Overall, this training seemed to be high quality because:

- The teaching methods seemed thoughtful – the trainer varied the way that she asked questions so that sometimes all of the trainees responded and sometimes individuals who seemed to be struggling or who were less engaged were asked to respond. She also had two trainees perform in a skit about treating diarrhea that seemed to keep trainees engaged. The training went through a series of diarrhea case studies that seemed nuanced and helpful.

- It was very high energy – roughly every 30 minutes, there was a break to dance and sing together and all of the audience seemed excited during these breaks.

- The training was held in a bright, cool room (kept cool by fans) and there was a projected presentation for trainees to follow along with.”

Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014

- 8

Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014, conversation with Alfred Wise. Not included directly in site visit notes.

- 9

Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014, conversation with Alfred Wise. Not included directly in site visit notes.

- 10

“To operate as a Living Goods CHP, applicants must:

- Attend two weeks of training and pass the test at the end

- On passing the test, invest UGX 82,000 in the tools and initial inventory to build their business. A 6-month loan is available, with a UGX 25,000 deposit required up-front to get commodities worth 54,000 UGX and a phone worth 270,000 UGX.

- Commit to spending at least 2 hours per day visiting households in their zone.”

Living Goods CHP Profile and Expectations, Pg 1.

According to Google, UGX 82,000 was worth USD 31.48 on September 4, 2014.

- 11

“Living Goods equips CHPs with:

- Free training for 2 weeks on health and business.

- A business-in-a-bag with tools and branding materials

- A touch phone to support the CHP’s health work

- A start-up loan for the purchase of initial products, to be repaid over 6 months

- Ongoing Stocking of products at Living Goods branches

- On-going training as they work”

Living Goods CHP Profile and Expectations, Pg 1.

“Our business-in-a-bag provides micro-entrepreneurs with all the tools they need to launch a thriving Living Goods franchise. Their startup kit includes a branded duffle bag, uniforms, signs for their home store, a display locker, and basic health and business tools. Couple that with a robust two-week training course and ongoing marketing and mentoring support and you have an army of motivated agents bringing life-changing products to the doorsteps of the poor.” Living Goods Business-In-A-Bag.

- 12

“After initial training, Living Goods will provide in-service trainings for CHPs. This is an excellent opportunity for Branch Staff to expand their own learning as well as check in with CHPs on challenges and successes.” Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 9.

“Agents also attend one day of training every month to review key health or business topics, discuss operational issues, hear about new policies and learn about new product offerings.” Living Goods Training & Coaching.

- 13

- The number of applicants that Living Goods interviews for each trainee was mentioned to us during a conversation with Alfred Wise on the Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014. Not included directly in site visit notes.

- “At the end of training, LG tests trainees’ health knowledge and Android skills. Usually, about 5-10% of trainees fail these tests.” Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014

- 14

- Living Goods Ugandan Monthly Sales

- Email from Chuck Slaughter, Founder and President, Brad Presner, Director of Analytics, and Lisa McCandless, Director of Development, Living Goods, October 6, 2014

- 15

“It is your responsibility to hold your branch’s CHPs to these standards:

1. 100% stocking of essential items (ORS + zinc, amoxicillin, ACTs)...”

Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 9. - 16

- “For sales data, Branch Staff can run reports on performance directly from the POS. The IT team will also communicate with you on the purchase performance of CHPs each month.” Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 9.

- The document later explains that the POS is the system that branches use to record sales to CHPs. Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 14.

- Living Goods confirmed that the sales data represents sales from Living Goods to CHPs in Email from Chuck Slaughter, Founder and President, Brad Presner, Director of Analytics, and Lisa McCandless, Director of Development, Living Goods, October 6, 2014.

- 17

- Chuck Slaughter, conversation with GiveWell, July 29, 2014.

- Email from Chuck Slaughter, Founder and President, Brad Presner, Director of Analytics, and Lisa McCandless, Director of Development, Living Goods, October 6, 2014

- 18

Email from Chuck Slaughter, Founder and President, Brad Presner, Director of Analytics, and Lisa McCandless, Director of Development, Living Goods, October 6, 2014

- 19

- Data from Living Goods Ugandan Monthly Sales, summarized in sheet ‘Analysis by GiveWell.’

- Living Goods provided a list of sales for 974 products, many of which are listed multiple times. Based on the names, we categorized these into product type. We believe that we have categorized correctly for a large portion of the products, but we may not have been fully accurate. For 0.55% of sales, we were not confident enough to guess a category. We have converted from Ugandan shillings to US dollars.

- Note: Units may be misleading for products that are sold in larger packets. For example, in one product, 1 unit contains 10 ORS dosages. Some food products come in larger packaging in which 1 unit may contain 10 or 30 smaller packets. (Email from Chuck Slaughter, Founder and President, Brad Presner, Director of Analytics, and Lisa McCandless, Director of Development, Living Goods, October 6, 2014)

- Data on sales margins from Living Goods Product List (July 2014).

- 20

“Over the last four years we built a network in Uganda of over 1,000 sales agents and are on our way to establishing a self-funded system for fighting disease and poverty in the developing world. With Uganda on the road to sustainability, we were ready to take what we learned and open a second country - Living Goods Kenya began operating in 2013.” Living Goods Where We Work.

- 21

Email from Chuck Slaughter, Founder and President, Brad Presner, Director of Analytics, and Lisa McCandless, Director of Development, Living Goods, October 6, 2014

- 22

Data from Living Goods Kenya Monthly Sales, summarized in sheet ‘Analysis by GiveWell.’

Living Goods provided a list of sales for 82 products. Based on the names, we categorized these into product type. We believe that we have categorized correctly for a large portion of the products, but we may not have been fully accurate. For 2.3% of sales, we were not confident enough to guess a category. We have converted from Kenya shillings to US dollars.

- 23

“BRAC and LG agents go house-to-house, teaching families better health practices across the core impact areas noted above. Agents evaluate and advise homes on nutrition, family planning, hygiene practices, use of key preventative methods including bed nets, water treatment, clean stoves, and solar lights.” Living Goods-BRAC Draft Scale Up Concept Note (August 2014), Pg 4.

- 24

“During household visits agents check children’s health and use ICCM guided assessment to address any illness.” Living Goods-BRAC Draft Scale Up Concept Note (August 2014), Pg 4.

Details on ICCM at WHO/UNICEF Integrated Community Case Management.

- 25

Living Goods told us that CHPs carry out these activities while we were on the Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014. Not included directly in site visit notes.

- 26

“Agents provide all clients with their mobile phone number so customers may reach them promptly when a child is ill or they need health commodities.” Living Goods-BRAC Draft Scale Up Concept Note (August 2014), Pg 4.

- 27

“As noted above, agents seek to identify and register and support pregnancies. LG and BRAC provide small financial incentives for each registration and for key pre and post-natal visits. CHPs make two to three ante natal visits to educate the expectant moms, check for danger signs and risk factors, encourage ANC checks at health centers, promote the use of iron folate and a healthy diet, prophylaxis for malaria, and help clients plan for their delivery and newborn care. We sell clean delivery kits to help prevent sepsis.” Living Goods-BRAC Draft Scale Up Concept Note (August 2014), Pg 5.

- 28

“As the majority of reported deaths are occurring in the first month, we will place a particular emphasis on post-natal visits and proper newborn care as noted above. Agents must visit the new moms as soon as possible after the delivery, and once more in the first week. We provide a free cozy cap to every new mom who notifies their CHP when they are in labor or within 24 hours of the birth to help ensure the PNCs happen promptly.” Living Goods-BRAC Draft Scale Up Concept Note (August 2014), Pg 5.

“As they do now, agents will register pregnancies as early as in term as possible, provide basic ante natal care and encourage ANC visits at public health centers, deliver maternal vitamin supplements, help all mothers deliver in proper facilities, and importantly, ensure proper newborn care practices.” Living Goods-BRAC Draft Scale Up Concept Note (August 2014), Pg 3.

- 29

“Agents provide community health education through regular community health talks, especially leveraging connections with local community groups, schools, places of worship, and support from local leaders and council members.” Living Goods-BRAC Draft Scale Up Concept Note (August 2014), Pg 4.

“It is your responsibility to hold your branch’s CHPs to these standards:...

2. Carry out at least 2 community events each month.” Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 9. - 30

“The Branch Manager and Assistant Manager should meet with or talk to each CHP in their branch at least once a month.” Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 9.

- 31

“It is your responsibility to hold your branch’s CHPs to these standards:

3. Properly report health data (pregnancy registrations, under 5

treatments, etc.) each month.” Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 9. - 32

Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014, conversation with Betty Kyazike. Not included directly in site visit notes.

- 33

Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 10-13.

- 34

Living Goods Draft Branch Management Handbook, Pg 10. 165,000 UGX converted to USD with Google.

- 35

Email from Chuck Slaughter, Founder and President, Brad Presner, Director of Analytics, and Lisa McCandless, Director of Development, Living Goods, October 6, 2014

- 36

Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014, conversation with Alfred Wise. Not included directly in site visit notes.

- 37

“CHPs maintain a family register that contains information such as: whether a pregnant woman, child under 1 year old, and/or child under 5 years old lives in a household, the household’s phone number, and the last time the CHP visited the household. The CHPs said that at the beginning of their work day they check the register and prioritize visiting priority households (e.g., households with young children or pregnant mothers) that they have not visited recently. In the future, the family register could be kept on CHPs’ Android phones exclusively. Currently, some CHPs still use paper registers because they have not transferred all of their records to their phones.” Notes from GiveWell site visit to Living Goods and BRAC, October 2014

- 38