Our Report

Table of Contents

Published: April 2024

Summary

What do they do? This review focuses on Helen Keller International (“Helen Keller”)’s vitamin A supplementation (VAS) program in sub-Saharan Africa. Helen Keller provides funding to governments to deliver VAS campaigns for preschool age children. It also provides technical support on various aspects of these campaigns including planning, training of distributors, and promoting awareness of the campaign, and conducts monitoring to understand how many children are reached (more).

We recommend Helen Keller International’s VAS program as a top charity because:

- We believe that VAS is a highly cost-effective program. (More)

- Helen Keller has a long track record of supporting VAS, which positions it well to carry out and expand VAS programs. (More)

- Transparency—Helen Keller shares significant information about its work with us. (More)

Our main reservations about Helen Keller International’s VAS program are:

- While we think it is valuable overall, we have some reservations about Helen Keller’s monitoring. This reduces our confidence that its programs are reaching a high proportion of targeted children. (More)

- We have sometimes found information from Helen Keller hard to interpret. This means that we have not been able to understand differences between the delivery models used in different locations in as much detail as we would like. (More)

This assessment of Helen Keller is based on the following components:

What do you get for your dollar? GiveWell believes that Helen Keller’s VAS program is one of the most cost-effective programs that donors can support. As of February 2024, we estimate that it costs between ~$1,000 and ~$8,500 (varying by country) to avert a death through Helen Keller-supported VAS campaigns. We think VAS is cost-effective because there is evidence that it reduces child mortality and it is very cheap to deliver.

We have a number of uncertainties about the evidence for VAS in general, including whether it is still effective in the context of improved child health since the studies we use in our analysis were conducted and some studies unexpectedly finding small or no effects. See our separate VAS report for more details.

What information has Helen Keller shared on its program? We ask organizations that we fund to share monitoring data and other detailed information on their programs. We use the data as inputs in our cost-effectiveness analysis, and its quality and reliability also inform our overall assessment of the program. For Helen Keller, this includes post-campaign surveys to estimate the proportion of children reached, cost data, and information on other actors’ likely spending on future campaigns in the countries where it supports VAS. (More)

We think this information is valuable overall, and provides some evidence that Helen Keller’s programs are reaching a relatively high proportion of targeted children at low cost. However, we have some reservations that reduce our confidence in it:

- Helen Keller’s surveys have only covered some campaign rounds, and in some surveys only some regions or districts are included. We do not have a strong understanding of why these rounds and locations were selected. Implementers may also know which locations will be surveyed in advance, and have a stronger incentive to ensure high coverage in the surveyed locations. This raises concerns that the monitoring data we’ve seen may not be representative, and that non-surveyed locations might have lower coverage rates. (More)

- Our analysis of Helen Keller’s cost and coverage data suggests a wide variation in costs between different locations where its program operates. We think it’s possible that this is because the cost information we received from Helen Keller was not comprehensive of all costs from other actors contributing to its campaigns, although Helen Keller has also suggested other explanations that we think are plausible. (More)

What is GiveWell’s qualitative assessment of Helen Keller? We make qualitative assessments of our top charities alongside our cost-effectiveness analyses to inform our grantmaking. Overall, our assessment of Helen Keller on most criteria is average, and we have not assessed it as standing out in any dimension (although we see all GiveWell top charities as exceptional relative to the majority of organizations). Factors informing our assessment include (more):

- Our impression has been that Helen Keller is not as concerned as GiveWell about the monitoring issues we identify above.

- Helen Keller has a long track record of delivering VAS, with in-country presence and relationships with ministries of health in many high-priority countries.

- The information Helen Keller has shared with GiveWell is detailed, but we have sometimes found it challenging to fully understand and interpret.

1. What do they do?

1.1 In a nutshell

Helen Keller International (Helen Keller) supports programs focused on reducing malnutrition and averting blindness and poor vision in countries in Africa and Asia. It also provides vision screenings and distributes eyeglasses at schools in the United States.1

In this review, we focus only on Helen Keller's vitamin A supplementation (VAS) programs in a set of countries in sub-Saharan Africa where Helen Keller operates with funding from GiveWell donors.2

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that children aged 6 to 59 months in areas where vitamin A deficiency (VAD) is a public health problem receive vitamin A supplements two to three times per year to reduce child mortality.3 Helen Keller supports countries' VAS programs mainly by providing funding to support government-run campaigns and providing technical assistance on these campaigns.

1.2 What is Vitamin A supplementation (VAS)?

Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) is a common condition in low and middle income countries that can cause stunting, anemia, and blindness. It can also increase susceptibility to infection and lead to death.4 Deficiency is most common where diets include few animal products and little vitamin A-fortified food.5

Vitamin A supplementation (VAS) involves distributing vitamin A capsules to children aged 6 - 59 months in areas with high rates of deficiency. The World Health Organization recommends that children in high risk settings should receive VAS every four to six months.6

As of February 2024, VAS is one of GiveWell’s top recommended programs. We think VAS is highly cost-effective because:

- There is evidence that VAS significantly reduces child mortality (we estimate ~4% to ~12% in countries where GiveWell supports Helen Keller for VAS).

- VAS is very cheap to deliver (around $1 per capsule delivered).

- In addition to preventing deaths, we think VAS probably provides additional benefits like increased income in later life, vision benefits, and costs averted from treatment of illness.

We discuss the evidence for VAS in detail in our separate report on VAS.

1.3 How VAS distribution works

VAS distributions use one of two main approaches7 :

- Mass campaigns involve large-scale distribution of VAS to households in a short period of time. In these campaigns, VAS is often co-delivered with other public health interventions by community health workers, including deworming, polio vaccination, "mop-up" immunizations (for children who have missed scheduled immunizations), and screening for severe acute malnutrition and moderate acute malnutrition.8 The campaigns we have seen occur twice a year.9

- Routine delivery of VAS involves giving children VAS at primary health facilities and at other touchpoints they might have with the national healthcare system (e.g. during routine immunizations).

Helen Keller supports both kinds of VAS delivery, but focuses on supporting campaigns. The specific delivery model used in VAS campaigns supported by Helen Keller varies by location. The main types of delivery we have seen are:

- Door-to-door campaigns: Community distributors go door-to-door in target communities to deliver VAS to children in their homes. As of February 2024, this is the main strategy used in eight of the 10 countries where GiveWell has funded Helen Keller to support VAS campaigns.10

- Fixed + outreach campaigns: In these campaigns, caregivers bring their children to health centers or other fixed distribution sites to receive VAS (often with a package of other health services). These campaigns are often delivered alongside outreach strategies to inform caregivers that a campaign is happening and encourage them to bring their children to the distribution site.11 As of February 2024, this is the main strategy used in two of the 10 countries where GiveWell funds Helen Keller’s VAS work (Nigeria and Kenya).12

This spreadsheet lists the distribution methods and co-delivered interventions for VAS mass distribution campaigns that Helen Keller supported with GiveWell-directed funding in 2018 through 2021.

Historically, GiveWell asked Helen Keller to use GiveWell-directed funding for mass campaigns only, since we are most confident that campaigns are a reliable way to achieve high levels of VAS coverage.

More recently, Helen Keller has begun experimenting with new delivery models to reduce costs while maintaining high coverage (examples in footnote).13 Helen Keller has also reported that it is planning to transition towards greater integration of VAS in the routine healthcare system in some locations. Our understanding is that this shift has generally been in response to requests from national ministries of health. The most specific example we’ve seen is in Côte d’Ivoire, where Helen Keller reports it plans to gradually transition some districts to a routine-only delivery model (without campaigns) between 2023 and 2027, although we do not have a strong understanding of what this process will involve (details in footnote).14 As of February 2024, we expect this shift could play a role in our understanding of Helen Keller’s VAS program in the future in some locations, but we haven’t yet seen evidence to know how significant a change this will be.

Other relevant information about how VAS distributions work:

- VAS has often been “piggybacked” onto existing public health campaigns, and historically polio vaccination campaigns have been a common vehicle for this.15 Our understanding from Helen Keller is that polio campaigns have been decreasing in frequency in recent years16 , and therefore we expect that this will become less common in the future.

- Health workers implementing VAS programs are instructed to cut vitamin A capsules open with scissors and squeeze the contents of the capsules directly into children's mouths.17 Health workers are also instructed to ask caregivers about the age of the child in order to provide the correct dosage of vitamin A: 100,000 IU (international units) for 6-11 month-old infants, and 200,000 IU to 12-59 month-old children.18

1.4 Helen Keller’s role in VAS campaigns

Overview of activities

Helen Keller provides grants to governments to fund the delivery of VAS campaigns (more) and gives technical assistance to assist with various aspects of campaign delivery (more). It also conducts monitoring after campaigns to understand what proportion of children were reached (more) and advocates for the importance of VAS to national governments (more).

In the countries where Helen Keller works, it collaborates with national and regional governments and two other VAS implementing organizations (UNICEF and Nutrition International) to support VAS.19

- National and regional governments manage the VAS campaigns and are responsible for each country’s overall VAS strategy. Our understanding is that the workers implementing VAS programs are employees (or volunteers paid a stipend) recruited by the government, usually referred to as “community distributors”.20 When delivering VAS campaigns, community distributors are usually organized in pairs.21

- Helen Keller, UNICEF, and Nutrition International typically focus on providing funding and technical support for different regions or activities within each country.22 Our understanding is that this process is coordinated in part by the Global Alliance for Vitamin A (GAVA), a forum in which Helen Keller, UNICEF and Nutritional International are the three core partner agencies.23

- The vitamin A capsules used in the campaigns are donated by Nutrition International, using funding from the Government of Canada.24

From 2018 through 2021, Helen Keller supported VAS campaigns in nine countries25 using GiveWell funding. This spreadsheet summarizes the campaign locations, interventions, and methods used in that period. In April 2023, GiveWell also recommended a $6 million grant to Helen Keller to expand its VAS program in Madagascar (more details in our grant page).

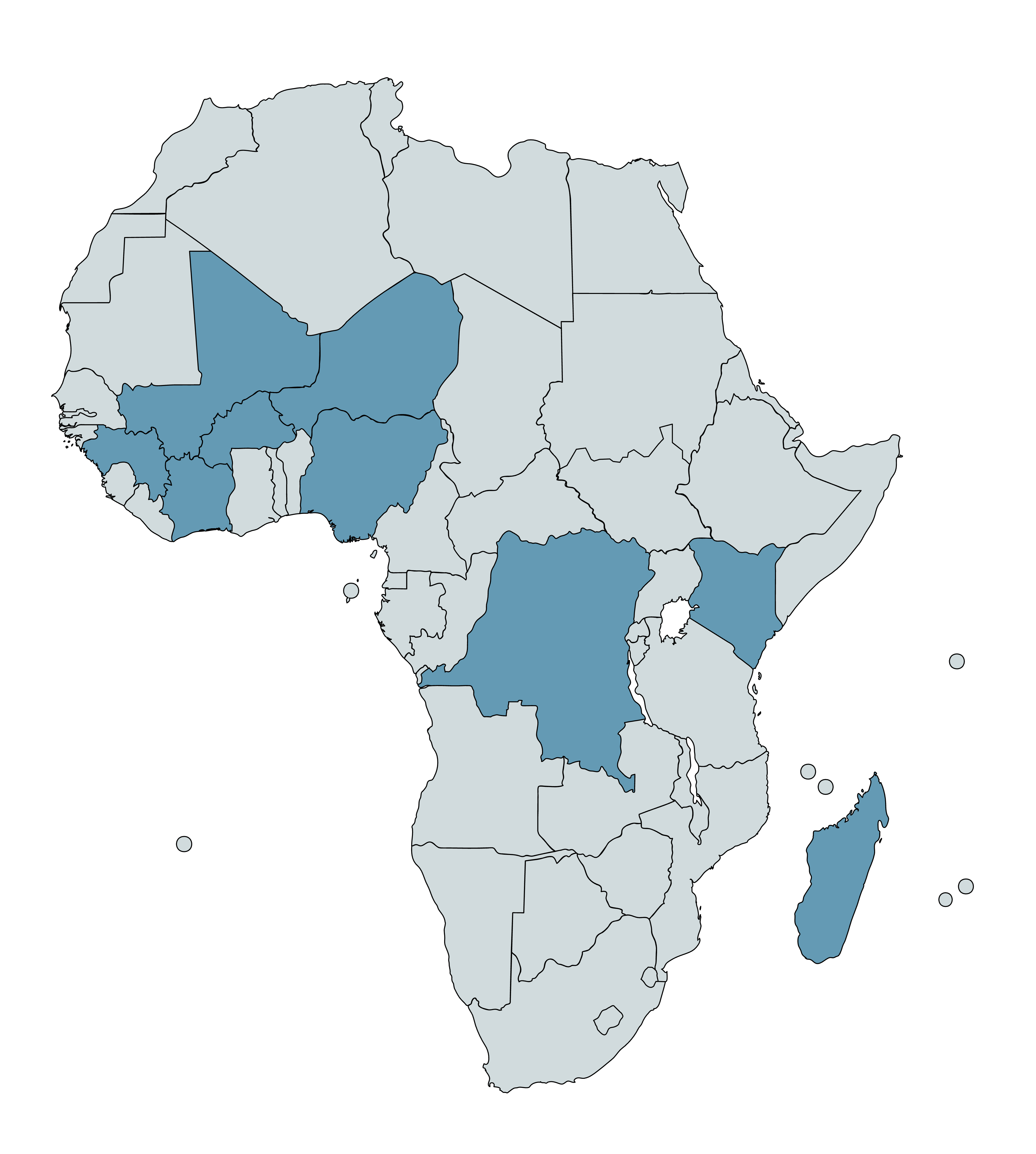

Countries with Helen Keller-supported VAS campaigns between 2018-21, plus Madagascar, are highlighted in blue.26

Funding campaigns

In the specific regions it supports, Helen Keller provides grants to governments (either national or regional) to fund the cost of delivering VAS campaigns.27 The funding is used for various activities needed to deliver the campaign (e.g., training health workers, and health worker per diems), as set out in “sub agreements” that dictate the legal responsibilities of the government and Helen Keller.28 The level of funding and the specific activities covered have varied across countries and over time—see this spreadsheet for a breakdown of Helen Keller’s spending on grants (‘Sub agreements’) from 2018 to 2021, by country.

Technical assistance

Helen Keller provides technical assistance to national and local governments to support the effective delivery of campaigns.29 Our understanding is that this assistance has taken different forms in different locations and over time, although we don’t have a strong understanding of exactly which activities Helen Keller has conducted in each location. Activities include:

- Micro planning: Helen Keller reports that it works with governments to develop “micro plans” approximately six weeks before campaigns take place. These contain plans for the target populations, staffing requirements, logistics processes, and other operational aspects of the campaign.30

- Training: Helen Keller works with national and local health authorities to coordinate and deliver the training for VAS campaigns. Our understanding is that this usually takes the form of a training of trainers (TOT) model, with Helen Keller training supervisors at a national level, who cascade the training down to district health management teams, health workers, and the community distributors who deliver the campaigns. Helen Keller’s role also includes developing and editing training tools, building on lessons from previous campaigns.31

- Social mobilization: Helen Keller conducts (and/or funds the health authorities to conduct) several activities to promote upcoming campaigns. These activities usually last for 5 days, beginning 3 days before the start of a campaign and running into the first 2 days of the campaign. Helen Keller reports that the mobilization campaigns used vary by country, but can include radio, town criers, banners and posters, and communication with traditional and religious leaders.32

Monitoring and evaluation

Helen Keller conducts monitoring to assess whether campaigns are being conducted effectively and reaching children as intended. The monitoring we have engaged with are its post-campaign coverage surveys to understand what proportion of children were reached with VAS. See the section below for a detailed discussion of these surveys.

Helen Keller also reports that it funds independent monitors to assess whether distributors are reaching all the locations they are supposed to reach, and supervision activities (jointly delivered with teams from national and local health authorities) to monitor progress during the campaign (details in footnote).33 We have not engaged with these processes in detail and we do not have a strong understanding of what kind of information they produce.

Advocacy

Helen Keller encourages national governments to prioritize budgeting for and implementing VAS mass campaigns,34

and advocates for routine distribution of vitamin A supplements through health facilities.35

1.5 Helen Keller’s spending on VAS campaigns

Helen Keller's work on VAS campaigns in 2018 through 2021 was primarily funded by GiveWell-directed funding.36 This spreadsheet contains a summary. In short, in 202137 :

- Helen Keller spent a total of $15.1 million on VAS campaigns, up from $7.6 million in 2020 and $5.8 million in 2019.38

- By location, Helen Keller spent between roughly $1 and $2 million each in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Niger, and Nigeria.39

- By category, Helen Keller spent around 42% on grants to governments for program implementation ("sub-agreements"),40 50% on direct program costs (including campaign logistics, training, monitoring, personnel, travel, equipment, and supplies), and 8% on overhead costs.41

- Helen Keller also spent $0.5 million on delivery of VAS through approaches other than campaigns: around $100,000 to $200,000 per country in Cameroon, Senegal, and Sierra Leone.42

2. Monitoring and information sharing

2.1 Overview

GiveWell asks organizations that we fund to share detailed information on their programs. The aim of reviewing this information is to assess how much the program costs, whether the program is being conducted to a high quality, and whether it is reaching recipients as intended. We use data from these reviews as inputs in our cost-effectiveness analyses, and the quality and reliability of the information we’ve seen also inform our qualitative assessment of the program.

Helen Keller has shared detailed information that we use to evaluate its VAS program including:

- Monitoring data from previous campaigns, to estimate the proportion of children reached (more).

- Information on costs incurred on previous Helen Keller-supported campaigns (both Helen Keller’s and other actors’) (more).

- Information on other actors’ likely spending on future campaigns in the countries where Helen Keller supports VAS (more).

Overall, we think the information we have seen provides some evidence that:

- Helen Keller-supported campaigns are reaching a reasonably high proportion of children. The median reported percentage of children reached for Helen Keller’s previous campaigns is 85% (more).

- Helen Keller-supported campaigns are being delivered at low cost. Based on data on the proportion of children reached and the cost information that Helen Keller shares, we estimate that it costs around $1 in total (including both Helen Keller spending and other actors’ spending) to deliver each VAS capsule to a child in Helen Keller-supported campaigns (more).

- Helen Keller’s funding would probably not have been fully replaced by other actors in Helen Keller’s absence. As of February 2024, we roughly estimate that there is approximately a 20% - 45% chance (varying by country) that Helen Keller’s VAS funding would have been replaced by other actors (national governments and/or other NGOs) in Helen Keller’s absence. We adjust our cost-effectiveness analysis to account for the likelihood that Helen Keller’s funding is causing other actors to spend more or less on VAS than they otherwise would (more).

We have some reservations about this information that somewhat limit our confidence in it. We think that its main shortcomings are:

- Lack of comprehensive or fully representative monitoring. VAS campaigns take place twice a year, but Helen Keller normally only conducts post-campaign coverage surveys after one campaign round in each country (and sometimes only in certain regions or districts). This is a concern because our best guess is that VAS coverage is likely to be lower in campaigns without coverage surveys than those with them, and that surveyed areas may not be representative. We account for this with a downward adjustment in our cost-effectiveness analysis of -17% (as of February 2024). This is a rough guess. (More).

- Possible lack of information on costs from other actors. We think that our estimates of the cost per supplement delivered in some countries are implausibly low. Our best guess is that this is because some other actors’ costs are not included in our analysis, although Helen Keller has also suggested reasons that we think are plausible. We therefore do not use our cost estimates from these countries in our analysis. We use an average cost per supplement figure from across other countries in our analysis instead (more).

- Limited results from supervisor audit procedure. Helen Keller surveys use an audit procedure, where a sample of households are re-visited by supervisors to check their responses against the original data. We think this procedure is a methodological strength, because it allows Helen Keller to check the accuracy of the data and because it is likely to encourage more accurate data collection. The results from this procedure that we have seen (based on a shallow review only) have been promising, but only about half of the coverage surveys report we reviewed in 2021 and 2022 reported results from the procedure (more).43

- Relatively non-detailed information on other actors’ likely future spending. While Helen Keller shares some information about other actors’ likely spending on future campaigns in the countries where Helen Keller supports VAS, this is less detailed than the information we have seen for some other programs. As a result, we think of our adjustments for other actors’ spending as very rough guesses (more).

2.2 Monitoring and evaluation

Overview

Helen Keller conducts coverage surveys to determine what proportion of children received VAS in previous campaigns. We use this data to understand whether the program is reaching children as intended, and as part of our estimates of the costs to deliver each capsule of VAS (discussed in our separate report on VAS).

Comprehensiveness

This spreadsheet contains all the results we have seen from coverage surveys of previous Helen Keller-supported VAS campaigns. We have reviewed coverage surveys from 2018 (the year Helen Keller began supporting VAS with GiveWell-directed funds) through 2021. We have also reviewed some surveys from 2022, although these are not comprehensive because not all 2022 surveys were available at the point we updated our analysis.44

Overall, the surveys we have seen in this period were for campaigns that represent approximately 54% of Helen Keller's total spending on VAS campaigns in 2018 - 2021.45 While this constitutes substantial evidence for the impact of Helen Keller's VAS campaigns, we note that these surveys are not comprehensive. This is a concern because our best guess is that VAS coverage is likely to be lower in campaigns without coverage surveys than those with them:

- Helen Keller usually conducts monitoring for only one of the two campaign rounds it delivers per country per year.46 Our understanding from Helen Keller is that VAS implementers may be aware of which campaign rounds will be surveyed in advance of the campaign.47 This raises a concern that implementers would be more incentivized to ensure high coverage in surveyed campaigns than non-surveyed campaigns (which have less oversight). This could result in overall coverage estimates being biased upwards.

- In some of Helen Keller’s surveys, only certain regions or districts are surveyed.48 We do not have a good understanding of how these specific regions or districts are selected, and what factors are used to determine this.49 This raises a concern that surveyed locations are not nationally representative, and therefore are not an accurate guide to measuring coverage. If VAS implementers know which locations will be surveyed in advance, they may also be more incentivized to ensure high coverage in surveyed compared to non-surveyed locations (the same concern as for non-surveyed campaign rounds discussed above). Helen Keller has previously told us about one example of managers dedicating extra attention to areas they knew would be surveyed, which increases our concern about this issue.50 Helen Keller has told us it is planning to pilot an approach in some locations whereby implementing teams will not know in advance whether a coverage survey will be conducted in their area,51 which we expect to mitigate this concern to some degree.

- We have heard feedback from Helen Keller that, in countries which have rainy seasons, its monitoring surveys tend to take place in the non-rainy season.52 This raises a concern that, if coverage is lower during campaigns conducted in the rainy season (e.g., because roads are flooded and some communities are harder to reach), the results we see may be systematically overestimating coverage.

As of February 2024, we account for these concerns in our cost-effectiveness analysis with a -17% adjustment for the quality of Helen Keller’s monitoring and evaluation (more below). Helen Keller has told us it is planning a change in its approach to improve survey representativeness and (as of November 2023) is actively working on what this will entail.53

One method we could use to corroborate Helen Keller’s monitoring data is to cross reference it with independent survey data (from the Demographic and Health Surveys) on the proportion of caregivers whose children received VAS. As of February 2024, we have begun this work but not yet finalized or published our analysis. We hope to investigate this question in more detail in the future.

Methodology

In Helen Keller's coverage surveys, data collectors visit a sample of households and ask household members whether the eligible children in those households received VAS during the relevant campaign. We have focused on understanding the methodology used in the coverage surveys conducted for campaigns in 2018 to 2021 that were supported with GiveWell-directed funds. Full details on the methodology used in those surveys are in this spreadsheet (‘Methods’ sheets).

In 2019, Helen Keller developed a revised coverage survey guide,54 with a new sampling methodology.55 Our understanding is that this methodology was used for most of the coverage surveys conducted in 2019 on, with exceptions noted in this footnote.56 The remainder of this section focuses on this methodology because it has been most commonly used in recent surveys and because we expect it to be used for the majority of future surveys we will receive from Helen Keller.

Key features of the coverage survey methodology are:

- Respondent selection: Helen Keller's 2019 - 2022 coverage surveys employed two-stage cluster sampling of households in the relevant study area.57

- In each survey, the study area was subdivided into smaller "enumeration areas," which were stratified as either urban or rural and in some cases by an additional quality (e.g., Helen Keller-supported or non-Helen Keller-supported).58 Enumeration areas were then selected randomly, generally with probability proportional to size, from each stratum.59

- Next, data collectors performed a census of all eligible households in selected enumeration areas.60 Census data was sent to the central supervision team, which randomly selected five to 15 eligible households (i.e., households that contained at least one child aged 6-59 months) per enumeration area.61

- We expect this selection protocol to result in a sample that is generally representative of the target population.

- Enumerators were instructed to survey all eligible children in selected households.62 To determine a child's age (and therefore if they are eligible to be surveyed), data enumerators are instructed to ask the child's caregiver for a health card or birth certificate that states the child's birth date. If documentation is not available, data collectors ask caregivers if they remember the child's birth date, and if the caregiver doesn't know the birth date, they ask about local events to estimate when the child was born.63

- If a selected household is unavailable, data collectors are instructed to return up to two additional times to attempt to interview that household.64 In nearly all the surveys we have reviewed, approximately 95% or higher of the targeted number of households were interviewed.65

- Survey design: Helen Keller has developed standard questionnaires,66

which it adapts for use in each country and translates into local languages. Each of the 2019-2021 coverage surveys we have reviewed included a pilot survey, during which questionnaires were tested and updated prior to survey implementation.67

The adaptation, translation, and piloting of questionnaires in each setting increases our confidence that they are administered appropriately and consistently across contexts.

- A potential source of bias in Helen Keller's coverage surveys is their heavy reliance on caregiver-reported responses. The questionnaire used during household interviews instructs data collectors to ask caregivers questions about VAS and other interventions received by children in their household, such as deworming.68 We believe that these responses are at risk of recall bias, as respondents must answer questions about multiple interventions and possibly multiple children. In many cases, the recall period for these responses was relatively short, about one month, while some surveys were conducted two months after the campaign.69 Caregiver-reported responses are also at risk of social desirability bias that could lead respondents to overreport VAS administration if they believe that this is the preferred response of data collectors.

- We would have more confidence in a survey that tested the reliability of reported responses against some objective measure. The questionnaire instructs data collectors to show household members vitamin A capsules and deworming tablets (or photos of these items) when asking questions about these treatments,70 but while these visual aids may improve accurate recall, they are not used to verify responses (for example, by asking respondents to identify these items before they are asked if eligible children received them).

- Survey implementation: Helen Keller contracts with independent consultants that recruit data collectors and supervisors and oversee survey implementation. Generally, data collectors and supervisors were not involved in VAS campaign implementation, though sometimes Helen Keller staff members are involved in survey implementation.71 Helen Keller's coverage surveys from 2019 to 2022 (we have not reviewed more recent surveys) included an auditing procedure in which supervisors were instructed to randomly select and then re-survey 10% of households in order to assess the accuracy of initial results, to which they were blinded.72 We see the inclusion of such a procedure as a methodological strength, both because it may encourage accurate data collection and because it provides a check on the accuracy of results. Generally speaking, the results from this procedure that we have seen (based on a light-touch review only) have found similar VAS coverage to the initial results and high correspondence (% agreement) between the audited data on VAS coverage and the main results (90+% correspondence). Correspondence on other audited measures (e.g., child age) has tended to be somewhat lower (~80% to ~100% depending on the measure and survey).73 These results generally increase our confidence in the accuracy of the data, although we have some open questions we have not fully investigated (details in footnote).74 However, not all coverage surveys have reported these results consistently—five of the nine surveys we reviewed in 2021 and 2022 reported audit results (of which only three reported correspondence), and four did not.75 Helen Keller has informed us it will include results from these audits in all future coverage survey reports.76

- Data capture: Data was collected electronically.77 One concern we have about coverage surveys in general is that data may be lost after being collected or that errors in aggregation at each level may be introduced. Electronic data collection enables data to be checked and aggregated centrally. We would guess that this reduces the chance of significant data loss or errors in aggregation, although we haven’t seen data on the proportion of data lost in Helen Keller’s surveys.

Detailed results

Overall, in coverage surveys we have reviewed from 2018 - 202278 :

- The median coverage rate for campaigns that were supported by Helen Keller using GiveWell-directed funds was 85%.79

- The lowest campaign coverage rate was 61%, from a VAS campaign in 2019 in a county in Kenya supported by Helen Keller.80 The highest campaign coverage rate was 94%, from the first VAS campaign of 2019 in six regions of Niger supported by Helen Keller.81

- Coverage rates for 66% of 2018-2022 campaigns with surveys were above 80%,82 which is the coverage rate targeted by Helen Keller for its VAS campaigns.83

See the “Coverage” sheet of this spreadsheet for a detailed breakdown of the data by country, year, and specific survey.

How Helen Keller’s monitoring informs our cost-effectiveness analysis

We use the data collected in Helen Keller’s coverage surveys in two ways in our cost-effectiveness analysis:

- As an input to calculate the cost per supplement delivered. We use estimates of the proportion of children reached in each country, alongside estimates of target populations of children aged 6 - 59 months and information on campaign costs (discussed below) to estimate the average cost to deliver one capsule of VAS to a child in Helen Keller’s campaigns.84 We discuss our approach in detail in this section of our report on vitamin A supplementation.

- Adjustment for quality of monitoring and evaluation. Although we think that Helen Keller's coverage surveys provide some evidence that a high proportion of the target population has been reached with VAS, our best guess is that the headline reported coverage figures are inflated because of the concerns we identify above. To account for this, we incorporate a -17% adjustment in our cost-effectiveness analysis. This figure is based on a rough percentage best guess of the impact of the concerns we have identified rather than an explicit model (reasoning in footnote).85

2.3 Cost data for Helen Keller-supported campaigns

Helen Keller has shared data on campaign costs incurred for each of the campaigns it has supported with GiveWell funding between 2018 and 2021. This includes costs incurred by Helen Keller itself (available here) and costs incurred by other actors (e.g., national governments, other NGOs) on these campaigns (available here).

We use this data (alongside estimates from the coverage surveys discussed above, and estimates of the target population of 6 - 59 month olds in locations where Helen Keller supports campaigns) to estimate the average cost to deliver one capsule of VAS to a child in Helen Keller’s campaigns. See this section of our report on vitamin A supplementation for a detailed discussion of our method and this spreadsheet for our calculations.

In summary:

- As of February 2024, we estimate that it costs approximately $1 to deliver a vitamin A capsule to a child in Helen Keller-supported programs (varying by country, from $0.80 in Mali to $1.39 in Guinea).86

- Our main uncertainties about the data we have seen are:

- Lack of information on other actors’ spending in some countries. Other actors (ministries of health, NGOs) also support VAS in the countries where Helen Keller works. We aim to incorporate all spending by these actors on Helen Keller-supported campaigns (based on cost data shared by Helen Keller), but these costs may not be comprehensive and we do not have an easy way to know how comprehensive they are.

- One reason to think we may be undercounting costs in some locations is that we calculate surprisingly low cost per supplement estimates (varying between $0.53 and $0.72) for Helen Keller-supported programs in Côte d’Ivoire, DRC, Kenya, and Nigeria. Although Helen Keller’s program in Kenya and Nigeria uses a fixed site delivery model (which we think could contribute to lower costs), we don’t know if this would explain the very significant cost differences (and cannot explain the surprising cost estimates in Côte d’Ivoire and DRC). Our best guess is that these figures are too low to be plausible, and one reason they are so low may be that some other actors’ costs are not included in our analysis,87 although Helen Keller has suggested reasons for these lower costs that we also think are plausible (details in footnote).88 Because of our uncertainty, we use an average cost per supplement figure of $1.02 (the weighted average of all other countries’ cost per supplement in our analysis) for these four countries.89 This is a somewhat conservative assumption, because there may be reasons that costs are lower in these countries. We plan to revisit this question in the future to understand what could be driving the differences in each location.

- Target population data. Our estimates of the number of children reached with VAS are based on data on the number of children aged 6 - 59 months in regions with Helen-Keller supported campaigns.90 Our understanding is that these figures are provided to Helen Keller by governments. We have not investigated this data in detail, and it is possible that these estimates are unreliable or outdated. In August 2022, we commissioned IDinsight to interrogate the target population estimates we use for Helen Keller's VAS program and others. As of this writing in February 2024, we have received the results from this work but have not yet concluded how they should affect our analysis or published the findings.

- Coverage estimates. In addition to cost data, our cost per supplement calculations also rely on estimates of the proportion of children reached from Helen Keller’s monitoring surveys. If these are inflated because of the concerns we identify above, we could be underestimating the true cost per supplement delivered.91

- Lack of information on other actors’ spending in some countries. Other actors (ministries of health, NGOs) also support VAS in the countries where Helen Keller works. We aim to incorporate all spending by these actors on Helen Keller-supported campaigns (based on cost data shared by Helen Keller), but these costs may not be comprehensive and we do not have an easy way to know how comprehensive they are.

2.4 Information on other actors’ VAS contributions

Helen Keller shares information with GiveWell about what other actors (e.g., national governments and other external VAS partners) have contributed (in previous campaigns) and are likely to contribute (on future campaigns) in countries where Helen Keller also supports VAS.92 This is distinct from the information on other actors’ costs on past Helen Keller-supported campaigns (discussed above). It relates to other actors’ spending in a whole country, not just on campaigns co-funded with Helen Keller, and includes future campaigns as well as previous campaigns.

We find this information valuable because we adjust our cost-effectiveness analysis to account for the likelihood that Helen Keller’s VAS funding is causing other actors to spend more or less on VAS than they otherwise would.

Overall, the information we have seen gives us some confidence that other actors would not fully be able to replace Helen Keller’s funding for VAS campaigns in Helen Keller’s absence (details in footnote).93 This in turn increases our confidence that Helen Keller’s spending results in a genuine increase in the number of children reached with VAS. As of February 2024, we roughly estimate that there is approximately a 20% - 45% chance (varying by country, from 20% in DRC to 45% in Guinea) that Helen Keller’s funding for VAS campaigns would have been replaced by other actors (national governments and/or external partners) in Helen Keller’s absence.94 This reduces our cost-effectiveness estimates by 18% (DRC) to 37% (Guinea).95 Intuitively, the reason that this is a significant negative adjustment is that we think there’s a substantial chance that the impact of Helen Keller’s funding is simply to free up other actors’ funding for other activities that we think are probably less cost-effective.

See this section of our separate report on VAS for more details on how we calculate these adjustments.

Our main reservation about the information Helen Keller shares about other actors’ likely spending is that it includes a relatively low level of detail. The report Helen Keller shares with GiveWell generally contains its expectations for the regions and activities that UNICEF and/or Nutrition International will be able to support in each country. It does not contain specific information on the amount of funding that each organization is able to contribute by country or how it reached its conclusions about the regions / activities that the other NGOs are able to support. Our understanding from Helen Keller is that this is because it is challenging to obtain information on other actors’ spending plans.

This level of detail is somewhat less than we have seen about other actors’ likely spending for some of GiveWell’s other top charities, and it reduces our confidence in our guesses about other actors’ spending.96

We therefore think of the resulting adjustments as rough best guesses in a context of high uncertainty.

3. Qualitative assessment

In theory, our recommendations are maximizing for one thing: total improvement in well-being per dollar spent. This is what our cost-effectiveness estimates intend to capture.

In practice, there are costs and benefits that we do not observe and are not estimated in our models. We make qualitative assessments to account for these unmodeled costs and benefits. We then use these assessments alongside our cost-effectiveness estimates to inform our funding recommendations.

As one tool for thinking through and communicating about impressions we have that aren't captured in our cost-effectiveness estimates, we assess each organization on eight dimensions on a four-point scale (“Stands out”; “Relatively strong”; “Average”, “Relatively weak”). We believe our top charities are exceptional relative to the majority of organizations and so these assessments are intended to capture differences among GiveWell top charities, rather than absolute rankings among all charitable organizations.

Overall, our assessment of Helen Keller is about average among GiveWell top charities on most criteria, and we have not assessed Helen Keller as standing out in any dimension. Our latest assessment (for 2023) is in the table below.

| Dimension | What does this capture? | Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Responses to our questions | When we ask the organization a question, do its answers generally either indicate that it has thought through the question before or show us why getting an answer is not important to understanding its work? | Average |

| Prioritization discussions | Do the organization's explanations about how it allocates funding among different locations and program participants seem to be aimed at maximizing its impact per dollar? | Average |

| Self-improvement and attitude toward mistakes | Does the organization proactively share information with us and publicly about mistakes it has made? | Average |

| Role in field | Is the organization producing research aimed at informing policymakers or other implementers? Does it participate in global conversations about its field of work? | Relatively strong |

| Responsiveness | Does the organization send us information by mutually agreed-upon deadlines? Is it responsive to our emails? | Average |

| Giving us feedback | Does the organization catch our mistakes and let us know, thus improving our research? Does the organization make useful suggestions for how we could improve our research process and cost-effectiveness models? | Average |

| Quality of information shared | Have the documents that the organization has shared with us contained significant errors? Has the organization told us things that were inaccurate? Has the information provided been easy to interpret and use? Have the organization's projections of when it would achieve its goals generally been accurate? | Average |

| Incorporating feedback from participants and last mile providers | How does the program collect feedback from program participants and from program implementers, i.e. those directly delivering the program? How does the program incorporate feedback to improve service delivery? | Average |

Our assessment is based on many conversations with Helen Keller over time and reviewing information it has shared on its program. Some examples of the factors informing our assessment are:

Self-improvement and attitude toward mistakes (average)

- Our ideal is that organizations we fund will be full thought partners in how to generate rigorous information to monitor their programs’ impact. We see Helen Keller as slightly below average compared to GiveWell’s other top charities on this metric.

- For example, we have felt that Helen Keller has been less concerned than GiveWell about issues we have raised about its monitoring (see above), although Helen Keller has told us it is planning a change in its approach to improve survey representativeness and (as of November 2023) is actively working on what this will entail.97

- We see it as a positive that Helen Keller has previously drawn attention to potential problems with its program. For example, Helen Keller has previously told us about one example of program managers dedicating more attention to locations that they knew in advance would be covered by a post-campaign survey.98 This kind of information increases our trust in Helen Keller and improves our ability to model the cost-effectiveness of its program. However, it has only done this sporadically.

- Overall, we see the information that Helen Keller has shared as reasonably detailed and reliable, in line with what we have seen from other GiveWell top charities.

- However, we have sometimes found the information Helen Keller has shared with GiveWell to be hard to fully interpret. This means we have not been able to understand some operational aspects of Helen Keller’s program as much as we would like. For example, Helen Keller reports using a hybrid approach to delivering VAS in Côte d’Ivoire and DRC, consisting of routine delivery through primary healthcare clinics for most of the year, with biannual “catch-up campaigns” to reach children who are missed.99 Our impression is that these are very similar to the conventional campaigns Helen Keller conducts in other locations, and we have not been able to understand how and why they are different. In 2023, GiveWell asked Helen Keller to share additional details on operational aspects of its program in each country in its annual narrative report, which has partly but not fully improved our understanding of how its program works.

- We have also found that some information Helen Keller has shared has been presented in a way that makes it hard to interpret. This includes inconsistent reporting in its coverage surveys (e.g., some surveys report findings from data audits and some do not),100 and a lack of clarity on where information is sourced from.

- Helen Keller is a large, multi-program NGO. It has staff and relationships with ministries of health in many of the countries where the greatest number of child deaths occur, which positions Helen Keller well to carry out and expand VAS programs.101 It is also one of the three core members of the Global Alliance for Vitamin A (GAVA) partnership.102

- We believe that it has a strong track record of identifying funding gaps for VAS and, when it has had resources to do so, scaling up programs quickly and reaching high coverage. For example, Helen Keller expanded its support for VAS campaigns with GiveWell funding from four countries in 2018 to nine countries in 2021.103 Our analysis of Helen Keller’s coverage surveys suggests that it managed to achieve generally high coverage in campaigns, even in countries where it was just beginning to provide support.104

Other points

- Helen Keller has taken the initiative in designing and testing different implementation models for VAS that are more closely integrated in routine healthcare delivery, and that can deliver high coverage at lower cost (examples in footnote).105 We see this as a positive because this effort is aligned with our goal of maximizing the cost-effectiveness of VAS programs.106 We have not yet fully analyzed the findings from these studies or considered their implications for how Helen Keller’s program will be delivered in the future.

4. What do you get for your dollar?

GiveWell recommends interventions and organizations that we believe are cost-effective in the sense of saving or improving lives as much as possible for as little money as possible. We summarize the full reasoning behind our cost-effectiveness analysis for Helen Keller in our separate report on VAS. In summary, as of February 2024, we think:

- It costs between ~$1,000 and ~$8,500107

to avert a death through Helen Keller-supported VAS campaigns. This equates to being approximately 9 to 59 times as effective as spending on unconditional cash transfers (GiveWell's benchmark for comparing different programs). This is because:

- VAS significantly reduces child mortality (we estimate ~4% to ~12%, depending on the location).108 This is based on a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, to which we apply some adjustments to account for our doubts about the evidence and changing health environments since the trials were conducted.

- VAS is very cheap to deliver (around $1 per capsule delivered).

- In addition to preventing deaths, we think VAS probably provides additional benefits like increased income in later life, vision benefits, and costs averted from treatment of illness.

See our VAS report for more details.

6. Sources

- 1

“Today, Helen Keller Intl helps children and families in 20 countries across Asia, Africa, Europe and the United States grow and eat nutritious food, stave off malnutrition, build strong immune systems, access life-saving medical treatments, and prevent and treat blindness and vision loss.

By providing the right support at the right time, we help millions of families and communities overcome longstanding cycles of poverty, helping them create lasting change in their own lives.” Helen Keller, ‘What we do’ page. Accessed June 2nd 2023.“42 states require regular vision screenings for students, but many school districts are unable to secure the budget to screen the youngest members of society. For just $35 a student, Helen Keller bridges this gap by partnering with schools to reach every child with a vision screening, and when needed, a pair of prescription eyeglasses.” Helen Keller, ‘Protecting Vision in the United States’ page. Accessed June 2nd 2023.

- 2

Between 2018 and 2021, Helen Keller supported VAS campaigns in nine countries with GiveWell funding. See this spreadsheet for details by country.

- 3

"In settings where vitamin A deficiency is a public health problem, vitamin A supplementation is recommended in infants and children 6–59 months of age as a public health intervention to reduce child morbidity and mortality (strong recommendation). The quality of the available evidence for all-cause mortality was high, whereas for all other critical outcomes it was moderate to very low. The quality of the available evidence for outcomes in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)- positive children was moderate for all-cause mortality." WHO Guideline: Vitamin A supplementation in infants and children 6-59 months of age 2011, p. 1.

- 4

“Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) impairs body functions and may cause death. Adverse health consequences may also include xerophthalmia (dry eyes), susceptibility to infection, stunting and anaemia (Sommer 1996; Rice 2004).” Imdad et al. 2010, p. 9.

Xerophthalmia (dry eyes), is “the leading cause of preventable childhood blindness” WHO, Global prevalence of vitamin A deficiency in populations at risk, 2009, Pg 1.

- 5

“Chronic VAD may develop when animal sources and fortified foods are limited, as in diets that rely heavily on vegetables and fruits (Ramakrishnan 2002).” Imdad et al. 2010, Pg 9.

- 6

“In settings where vitamin A deficiency is a public health problem, vitamin A supplementation is recommended in infants and children 6–59 months of age as a public health intervention to reduce child morbidity and mortality (strong recommendation).”

The 4-6 month recommended schedule is in the WHO guidelines on pg 5.

WHO Guideline: Vitamin A supplementation in infants and children 6-59 months of age 2011, pp. 1, 5. - 7

“Mass distribution campaigns are the main delivery mechanism for VAS. These campaigns are organized at least every 6 months…”

"Because mass campaigns take place only every 4 to 6 months, children who reach the age of 6 months between two campaigns, may have to wait several months before they get their first dose of Vitamin A despite being the most vulnerable age group."To remedy this, HKI is working closely with country-level health sector experts to add a contact point in national immunization calendars – at 6 months, when no other vaccination is scheduled.

"Additionally, HKI supports routine facility-based and outreach delivery of vitamin A for all children under 5 in countries where stronger health systems offer sufficient access to quality services. Few countries are ready for this approach and these still need to develop social mobilization actions to create demand to match the capacity to offer services." Helen Keller, VAS overview brochure, p. 2.

- 8

When paired with polio campaigns, these campaigns are known as “national immunization days” (NIDs). These campaigns are typically conducted door-to-door. When paired with deworming and other child health interventions, these campaigns are known as “Child Health Days” or “Child Health Week”. These may be either door-to-door or fixed site.

“In polio vaccination campaigns – also known as national immunization days (NIDs) – health workers go door-to-door providing oral polio vaccines. These campaigns generally occur one or more times per year. Because teams are already going door-to-door, it is relatively simple and inexpensive to add an additional person to each distribution team to deliver VAS to children aged 6 to 59 months.

Child health days (CHDs)

The term ‘child health day’ can refer to many different types of programs, but is generally some type of biannual event that provides a package of health interventions for preschool-aged children. There are two broad types of CHDs:- Mobile aka door-to-door distribution

- Mobile CHDs involve health workers going door-to-door to provide communities with vitamin A supplements and other health services. This strategy is operationally very similar to polio NIDs.

- Fixed-site distribution

- In fixed-site CHDs, caregivers must bring their children to health centers or other fixed distribution sites to receive the package of health services.

- Many CHD programs utilize a ‘fixed + outreach’ strategy, in which they implement outreach activities to encourage caregivers to bring their children to the fixed site to receive health services.”

GiveWell's notes from a site visit with Helen Keller to Conakry, Guinea, October 9-11, 2017, p. 3.

- Mobile aka door-to-door distribution

- 9

Note: the World Health Organization recommends VAS every four to six months, but we have not seen Helen Keller supporting campaigns at four-month intervals.

“In settings where vitamin A deficiency is a public health problem, vitamin A supplementation is recommended in infants and children 6–59 months of age as a public health intervention to reduce child morbidity and mortality (strong recommendation).”

The 4-6 month recommended schedule is in the WHO guidelines on pg 5.

WHO Guideline: Vitamin A supplementation in infants and children 6-59 months of age 2011, pp. 1, 5. - 10

Note: Helen Keller reports that six countries use a door-to-door campaign approach (Guinea, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, and Madagascar). See Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, figure 2 (pg. 7).

Helen Keller also reports that its program in DRC and Côte d’Ivoire uses a hybrid “routine + catch-up campaigns” approach, consisting of routine delivery through primary healthcare clinics for most of the year, with biannual “catch-up campaigns” to reach children who are missed. However, our understanding is that these campaigns are virtually identical to the conventional door-to-door campaigns that Helen Keller supports in other locations, with the only operational difference being more checks of vaccine cards to avoid double dosing. We therefore include these countries in our summary of countries where Helen Keller supports door-to-door campaigns. See Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, figure 2 (pg. 7).

Our understanding of the operational similarities between these campaigns and the campaigns in other countries is based on an unpublished conversation with Helen Keller, December 7th, 2023.

- 11

“Fixed-site distribution

- In fixed-site CHDs [Child Health Days], caregivers must bring their children to health centers or other fixed distribution sites to receive the package of health services.

- Many CHD programs utilize a 'fixed + outreach' strategy, in which they implement outreach activities to encourage caregivers to bring their children to the fixed site to receive health services."

GiveWell's notes from a site visit with Helen Keller to Conakry, Guinea, October 9-11, 2017, Pg 3.

- 12

See Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, pp. 21-22 (for Kenya) and pp. 26-7 (for Nigeria). Note that Helen Keller also supports campaigns using this approach in Tanzania (see pp. 29-30), but this is covered by other funding sources and has not used GiveWell funding.

- 13

Examples:

- Kenya: “Since 2020, Helen Keller has been conducting a study in Siaya county to compare the effectiveness of using community volunteers to distribute VAS routinely in their catchment areas versus distribution through facilities, and multiple outreach platforms including campaigns. The intervention is completed, and data analysis is currently underway. The report is expected to be completed before the end of quarter one in 2022.” Helen Keller, Annual Report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s Vitamin A Supplementation Activities, 2022, p. 7. GiveWell has since reviewed this report.

- Cameroon: “Two studies were conducted in Cameroon from January 2022 to July 2023. A bottleneck study of the twice-yearly VAS delivery through campaign took place from September to October 2022. Results from this study were crafted into actions to improve the SASNIM that took place in December 2022. From February 2022 to February 2023, Helen Keller supported the Ministry of Health in a project that implemented a self-monitoring approach in the routine health system. This approach aimed to strengthen the routine delivery of VAS in health facilities and increase caregiver uptake of VAS at health facilities in the health districts of Kaele and Guidiguis. In this project, administrative service utilization data were analyzed and compared to the census population data of target children who are due for VAS. If children were identified as nearing their due date for supplementation, the community health volunteers visited, reminded, and referred caregivers to the nearest health facility so that their child could receive VAS. If the child did not receive VAS within the month following the reminder/referral, a second visit was made to the household during the following month. During the review of administrative coverage data the end of every month, health workers organized and the community health workers would go to a targeted fixed point within the catchment areas with highest default rate (or, in other words, lowest VAS coverage of targeted children for that month). Community mobilization activities such as radio and community leadership announcements would promote/advertise that parents take their children to these fixed points if they were due or overdue for VAS. Using this approach for routine VAS distribution, Guidiguis and Kaele were successful in achieving high VAS coverage on a monthly basis throughout the pilot study (overall coverage throughout the study period: 87.6% in Guidiguis and 89.11% in Kaele). The cost per child supplemented with vitamin A in Kaele and Guidiguis was an estimated 497.11 FCFA (approximately 0.75 USD). The results from this study are available in a report and will be further developed into a paper for submission to an international journal for consideration for publication. These results are also currently being considered by the Ministry of Health and partners to inform the scale up of routine VAS delivery in Cameroon.” Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, pg. 36.

- 14

“The Ministry of Health aims to transition all 113 districts to this hybrid approach in the coming years. To ensure that the coverage of vitamin A supplementation (VAS) remains above 80%, Helen Keller Int’l will accompany this transition. In the initial years, some districts will continue distributing VAS through the traditional campaign approach, while others will be supported in adopting the hybrid approach combining routine delivery and campaigns. In certain districts, a combination of facility delivery, outreach distribution sessions, and delivery by community volunteers will be tested and later scaled up.” Helen Keller reports that it plans to work with the Ministry of Health to transition 75 of the 100 districts it plans to support to this latter model by 2027. See table 11, Helen Keller International, 2023 room for more funding report, pg. 19.

We do not have a strong understanding of what this transition will involve. Our initial understanding is that Helen Keller will be conducting an operational pilot in 8 health districts before expanding to the remaining planned districts. The pilot will test a model of routine VAS delivery that we understand is similar to the Cameroon pilot described in the footnote above. Health workers will conduct a census of children in their areas, and conduct outreach visits to children nearing their scheduled VAS date to encourage them to go to health clinics. Fixed post outreach events to deliver VAS will be conducted for areas with low coverage. However, we have not seen a detailed operational plan for this approach. This understanding is based on a conversation between GiveWell and Helen Keller, November 7th, 2023. - 15

“Initially, VAS coverage rapidly reached more than 80% of children aged 6 to 59 months in sub-Saharan Africa through its integration in door-to-door polio vaccination campaigns. However, as these campaigns began to phase out following progress in the eradication of polio in Africa in the 2010’s, VAS coverage started to decline.” Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, p. 6.

- 16

“When polio campaigns take place, the World Health Organization and the Global Polio Eradication Initiative cover the cost of the core teams, and VAS stakeholders “only” have to support the addition of one distributor. When there is no polio campaign, VAS partners usually support two distributors per campaign, resulting in significantly higher costs. The frequency of polio campaigns organized in Helen Keller countries continues to decline (see Table 2). The darkest cells in Table 2 show occurrences of polio campaigns where VAS could not be integrated, either for reasons of timeline or refusal of WHO. In situations where VAS could not be “piggy-backed” on polio campaigns, we had to increase funding support for VAS in these countries. Thus, in these situations, large variations occurred between the amounts originally budgeted by the country and amounts spent.” Helen Keller, Room for More Funding Report, July 2021, Pg. 7.

Note: although we would expect campaign costs to have risen over time because of fewer opportunities to piggyback on polio campaigns, GiveWell’s analysis suggests that Helen Keller’s cost per supplement actually fell between 2020 and 2022 (from $1.10 on average in our 2020 analysis to $1.02 in our 2022 analysis). We do not have a good understanding of the reason for the discrepancy.

- 17

"For distribution sites visited by an independent HKI supervisor, 86% met the criteria for minimum quality threshold for service delivery defined as 1) health worker used scissors to cut the capsule 2) health worker asked the age of the child 3) health worker squeezed the drops into the child’s mouth 4) health worker used the correct dose of VAS and 5) were there no stock-outs of VAC." Helen Keller VAS project year 1 report 2014 (unpublished).

See the guidelines for health workers in Helen Keller International, VAS supervision checklist: universal and Helen Keller International, Tanzania social mobilization toolkit: VAS administration guide.

- 18

Helen Keller International, Tanzania social mobilization toolkit: VAS administration guide:

- "Ask the age of the child to determine the appropriate dose of vitamin A (6-59 months) and whether the child is old enough for a deworming tablet (12-59 months)."

- "If the distribution point runs out of red (200,000 IU) capsules, two blue (100,000 IU) capsules can be given in place of one red capsule. If the distribution points runs out of blue capsules squeeze half the number of drops from a red capsule into the mouth of a child aged 6-11 months."

See additional guidelines for dosage selection in Helen Keller International, VAS supervision checklist: universal.

- 19

Other NGOs (e.g., the World Bank and World Health Organization) have also provided some financial support for VAS campaigns in some locations. Our understanding is that this is usually funding other interventions co-delivered with VAS. The level of support has varied by location and over time. See the explanatory notes on our cost per supplement analysis for further detail by country.

- 20

This understanding is based on many conversations with Helen Keller and other VAS stakeholders over time.

- 21

“Health workers distribute vitamin A capsules at health facility level, and community health workers are responsible for vitamin A distribution in communities, using either door-to-door visits or outreach distribution stations. Community distributors are usually organized in pairs and are equipped with tally sheets to record each capsule they distribute, indicating the age group and the sex of the child receiving it.” Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, pg. 10.

- 22

For a detailed description of each partner organization’s role by country in 2021 campaigns, and Helen Keller’s expectations for their roles in 2022 campaigns, see Helen Keller, Room for More Funding Report, July 2022. Examples:

- Cameroon: “Helen Keller resumed its support to the government of Cameroon for VAS during the second semester of 2021 in six regions: Centre, Littoral, West, South, Adamawa and East. These six regions represent close 3 million children 6-59 months of age (see Table 9), accounting for around 50 percent of all children in Cameroon. It also includes internally displaced persons (IDP) who are victims of insecurity in Northwest and Southwest regions. The other 4 regions were supported by Nutrition International (2) and UNICEF (2).” P. 9.

- Guinea: “No significant change occurred in the support provided by Helen Keller in Guinea. For the two rounds of 2022, Helen Keller supported 5 regions and UNICEF 3 regions.” P. 13.

- Mali: “In 2021, as UNICEF experienced funding gaps, Helen Keller was requested to support the additional region of Koulikoro for both semesters. Nutrition International also supported several regions. In 2022, it is planned that Helen Keller continues to support the 3 regions of Kayes, Ségou and Koulikoro for both semi-annual VAS distribution 2 rounds. UNICEF will support the remaining 8 regions and the Bamako District with various sources of funds, including some received from Nutrition International.” P. 15.

- 23

GAVA, ‘About’ page. “Core Partner Agencies: UNICEF, Nutrition International, Helen Keller International”. Accessed June 1st, 2023.

“These coordination forum[s] are always embedded in national coordination bodies chaired by the Ministry of Health. Decision on which regions each actor will support is taken based on availability of funds for each actor and historical presence of the actors in specific regions, for VAS or for other programs.” Helen Keller International, comments on a draft of this page, December 14th, 2023.Note that GiveWell only has a limited understanding of exactly how this coordination process works.

- 24

“Micronutrient Initiative (MI) (the name of the organization changed ~1 month ago to Nutrition International or NI) is only active in 4 of the 13 countries were HKI is operational, however MI provides the needed number of vitamin A capsules to all countries where HKI works. MI’s role essentially takes place at the national level, providing technical and policy guidance to governments. In most cases, MI delivers the vitamin A capsules to UNICEF, who organizes their management with the national government and ensures that they reach the field."

HKI country-level technical support related to vitamin A supplementation (unpublished), p. 2.“We have been a global leader in vitamin A supplementation since our inception 30 years ago, supporting governments to integrate VAS into existing health platforms and ensuring children are not missed with lifesaving VAS. We have led in setting the manufacturing standards and providing vitamin A capsules to eligible countries through the in-kind donation program – implemented with UNICEF, and with support from the Government of Canada – procuring and donating more than 10 billion capsules since 1997.”

Nutrition International, ‘Strengthening health systems to deliver lifesaving vitamin A’. Accessed May 2023. - 25

Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Niger, and Nigeria. In 2021, Helen Keller also used a small amount of funding to support non-campaign VAS activities in Cameroon, Senegal, and Sierra Leone. See Helen Keller International, 2022 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, pp. 5-6.

- 26

Created using https://www.mapchart.net/.

- 27

See this spreadsheet for a breakdown of Helen Keller’s budgets on campaigns from 2018 to 2021, by country. Budgets for "sub-agreements" are funds that Helen Keller plans to grant to governments for program implementation.

Helen Keller International told us that grants are typically provided to both national and subnational governments, with different activities covered by each.“The model used in most countries involves contracts with administrative units and at central level.

a) Sub-agreements at the national level facilitate coordination meetings, supervision of Ministry of Health staff at the central level in the field, and occasionally logistics for sending supplies from the national level to the field.

b) Sub-agreements at the administrative unit level cover training of actors, communication, social mobilisation activities, logistics, supervision, local coordination meetings and data validation meetings.” Helen Keller International, comments on a draft of this report, January 11th, 2024. - 28

“The resulting budget, along with the detailed information from the microplans, form the basis for sub-agreements signed with government entities.

These sub-agreements define in detail the roles and responsibilities of Helen Keller and the governments in the implementation of VAS activities and are mainly used for campaigns. Sub-agreement funds for government activities and staff represent approximately 70% of the total implementation costs and are established with local administrative entities. They describe the legal obligations of the government and all aspects of campaign implementation such as staff training, social mobilization, distribution, and data management. Sub-agreements also describe payment terms, milestones and deliverables associated with each payment.” Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, pg. 9.

Helen Keller notes that some funding for specific activities (e.g., coordination, planning meetings and data review meetings) is provided as “direct financial support”, paid for by Helen Keller, and not covered by the sub-agreement. Helen Keller, comments on a draft of this report, January 11th, 2024.

- 29

"To date, HKI’s VAS project has undertaken three main types of activities, which can roughly be categorized as disbursing sub-grants to the government, providing technical assistance, and engaging in advocacy efforts." HKI External Evaluation and HKI Response - Canada DFATD VAS Project 2015, p. 35 (unpublished).

- 30

“Helen Keller supports governments in developing microplans for both routine and campaigns. For routine, the process takes place at the beginning of every year with the government and partners. For campaigns, micro-planning begins approximately six weeks prior to the campaign (or routine mop up) activities and is characterized by several key inputs:

- Standardized micro-planning: Helen Keller has developed standardized guidelines to support governments to conduct this process, with daily objectives for distribution teams in both urban and rural areas of each supported region. These guidelines serve as a basic framework for accurately calculating the number of distributors, supervisors and social mobilisers needed. Implementing these standards ensures that the workload for each category of actor remains manageable, significantly increasing the campaign's chances of success.

- Comprehensive micro-plans: based on these standards, comprehensive micro-plans are developed with budgeted activities at all levels, from national level to health facilities. In addition defining the target populations and staffing requirements, these micro-plans specify supplies needs, address logistics processes, and create structured monitoring circuits.” Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, p. 9.

- 31

“Helen Keller is involved in coordinating and supporting training for all actors engaged in vitamin A supplementation at all levels of the health system. Our involvement includes the comprehensive review and improvement of training tools to capitalize on lessons learned from previous campaigns and the rollout of training tools. We work closely with Ministries of Health to facilitate training at all levels, usually training trainers ourselves at national level and supporting these trainers cascade the training down to the field level. This cascading approach ensures that health workers at facility level are trained by the district management teams, while community health workers are equipped with the necessary skills through training by health workers.” Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, pg. 9-10.

- 32

“Social mobilization: Promoting participation and buy-in from different social groups and local actors is critical to the success of the campaign. To inform communities about VAS campaigns and other related activities, we build the capacity of communication focal points and community mobilisers. Social mobilization activities, carried out by well-trained mobilisers from neighborhoods, villages, or communities, play a key role in behavior change. For campaigns, these mobilisers carry out door- to-door communication working closely with distribution teams, identify children, address possible refusals, and use their community connections to increase the effectiveness of distribution. These communication activities last for five days, starting three days before the start of the campaign and continuing for the first two days of campaign implementation. Helen Keller promotes the use of pre-identified mobilization channels tailored to specific environments. Local radio stations, administrators, health workers, educators, traditional and religious leaders, and town criers are used to disseminate information effectively. Banners and posters are used for visibility. Local radios are used to announce campaign dates and provide information on the benefits of vitamin A, the target age groups, administration methods, and other related activities.” Helen Keller International, 2023 annual report to GiveWell on Helen Keller International’s vitamin A supplementation activities, p. 10.

Examples of social mobilization and marketing materials:

- Helen Keller International, Tanzania social mobilization toolkit: VASD posters

- Helen Keller International, Tanzania social mobilization toolkit: mobilization script

- Helen Keller International, Tanzania social mobilization toolkit: mobilization script (Swahili)

- Helen Keller International, VAS television commercial: DRC (French)